Introduction to Panel Data

Data-Based Economics, ESCP, 2025-2026

Panels: Longitudinal Data

Motivation

A Simple Question

- Question: Does drinking coffee improve productivity?

- Data: We survey 1000 employees over 5 years.

- Cross-Sectional View: Compare Alice (drinks 5 cups) vs. Bob (drinks 0 cups).

- Finding: Alice is more stressed and less productive. \(\rightarrow\) Coffee is bad?

- Time-Series View: Follow Alice when she varies her coffee intake.

- Finding: On days she drinks coffee, she gets more done. \(\rightarrow\) Coffee is good!

- The Puzzle: Alice works in a high-pressure trading floor (stress causes coffee). Bob works in a library.

Panel data lets us separate the individual effect (Alice vs Bob) from the causal effect (Coffee vs No Coffee).

Data Dimensions: Time and Space

Two Dimensions

Until now, we have been rather loose about where the data comes from.

Trying to explain \(N\) observations: \(y_n = a + b x_n, n\in [1,N]\)

All these lonely observations, where do they all come from?

Individuals (Space)

(Cross-section)

Dates (Time)

(Time-series)

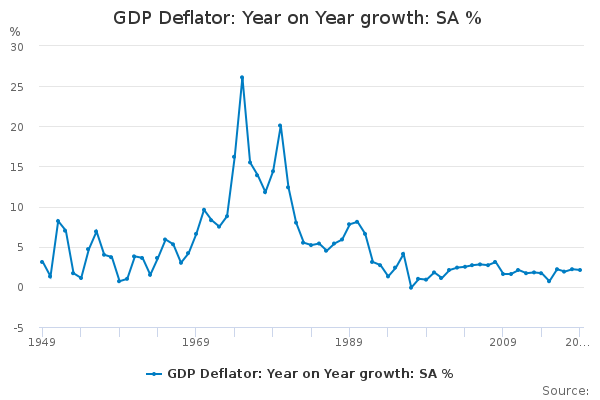

Time Series

- very simple study: structural break

- does regression on \([T_1, \overline{T}]\) yield (significantly) different results on \([\overline{T}, T_2]\)

- going further: time series analysis

- data is typically autocorrelated

- example (AR1) \(x_t = a + b x_{t-1} + \epsilon_t\)

Longitudinal Data / Panel Data

1. Repeated Cross-Sections

- Idea: Survey different random people each year.

- Example: “US Census 2000, 2010, 2020”

- Structure:

- Index individual \(i\) and time \(t\).

- But \(i=1\) in 2000 is NOT the same person as \(i=1\) in 2010.

- Analysis:

- We can study trends (e.g. inequality over time).

- But we cannot see who got richer.

2. Longitudinal (Panel) Data

- Idea: Follow the same individuals over time.

- Example: “Tracking the same 5000 families for 20 years (PSID)”

- Structure:

- \(y_{i,t}\) is person \(i\) at date \(t\).

- \(y_{i,t+1}\) is the same person, later.

- Power:

- We can control for unobserved characteristics of \(i\).

- We can study detailed dynamics.

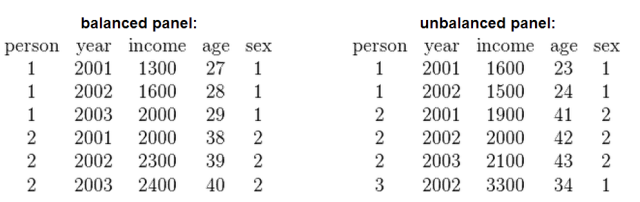

Balanced vs Unbalanced

- Balanced: all individuals in the sample are followed from 1 to T

- Unbalanced: some indivuduals start later, stop earlier

- Crude solutions:

- truncate the dates between \([T_1, T_2]\) so that dataset is balanced

- eliminate individuals who are not present in the full sample

- Not very good:

- can limit a lot the size of the sample

- can induce a “selection bias”

- Real gurus know how to deal with missing values

- many algorithms can be adapted

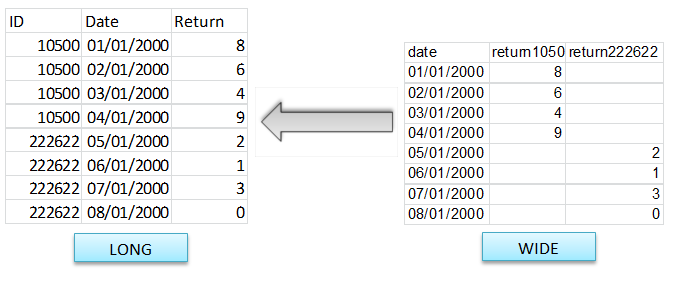

Long and wide format

- we tend to prefer here the long format (w.r.t id and date)

- there can be many columns though (for each variable)

Micro-Panel vs Macro-Panel

- micro-panel: \(T<<N\)

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID): 5000 consumers since 1967 (US)

- reinterview same individuals from year to year

- but some go in/out of the panel

- Survey of Consumer and Finance (SCF)

- …

- Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID): 5000 consumers since 1967 (US)

- macro-panel: \(T\approx N\)

- WIIW: 23 countries since the 60s (central, east and southern Europe)

The Curse of Heterogeneity

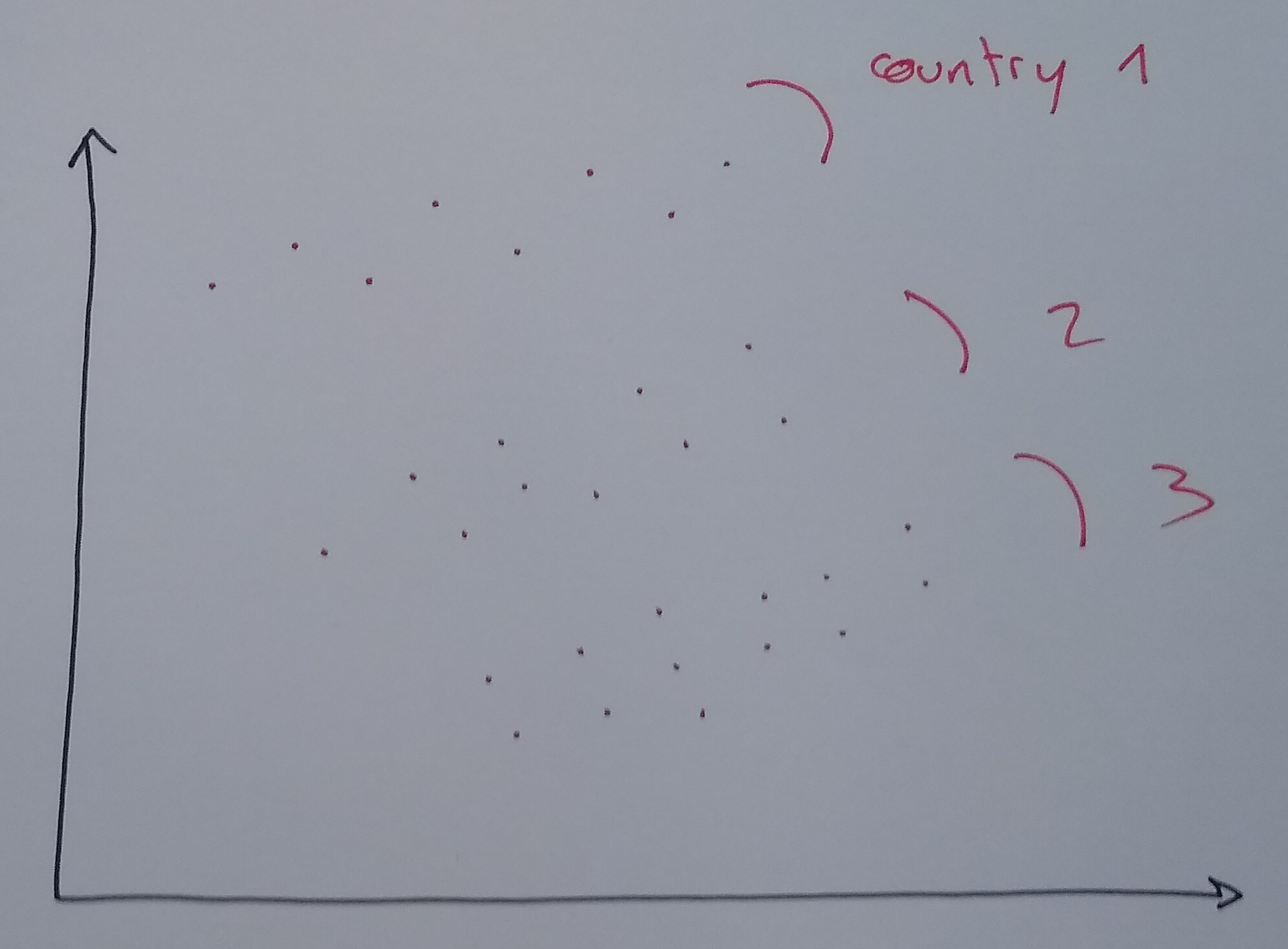

The Trap of Pooled Regression

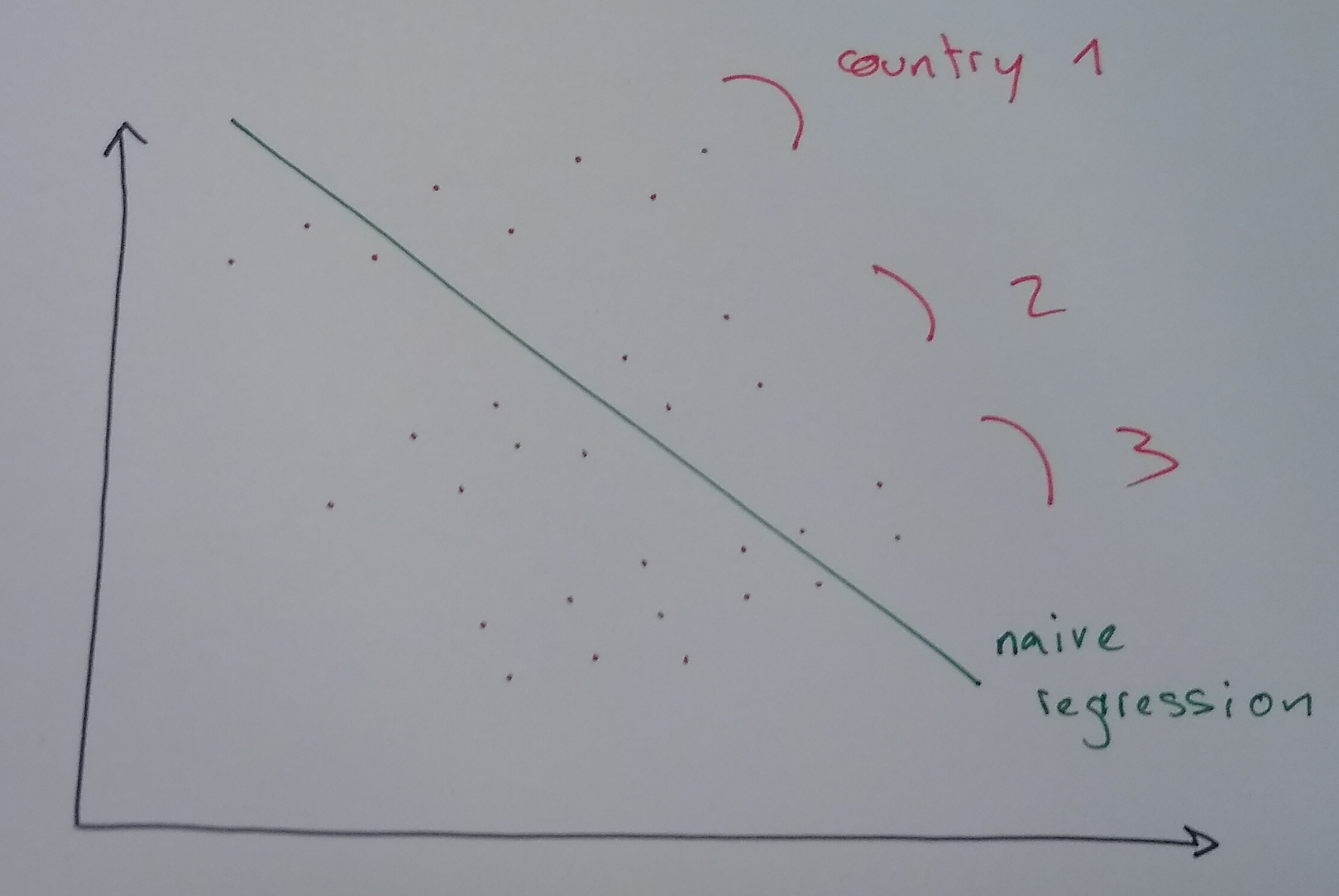

Context: We want to explain economic growth (\(y\)) using trade openness (\(x\)) for several countries.

The Mistake: “Pooled Regression”

- We throw all data points (all countries, all years) into one big pot.

- Formula: \(y_{i,t} = a + b x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\)

- Result: We find a negative relationship (the green line)!

The Reality:

- Look closely at each country (dots of same color).

- Within each country, the relationship is positive!

- Conclusion: We missed the “Country Effect” (Unobserved Heterogeneity).

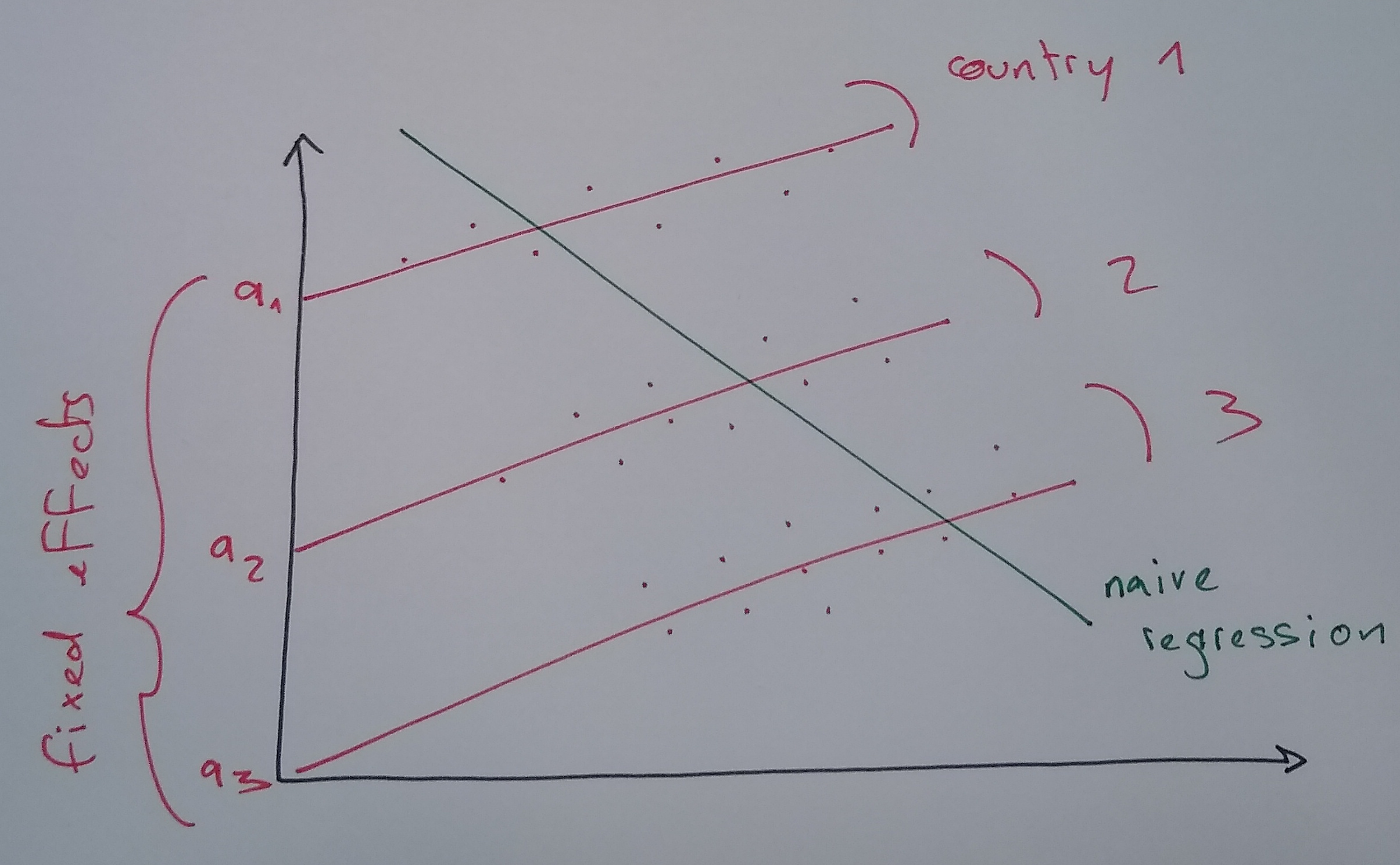

The Solution: Individual Fixed Effects

The Intuition

We admit that some individuals are just naturally “higher” or “lower” than others. We give each individual their own starting point (intercept).

The Model

\[ y_{i,t} = \underbrace{\alpha_i}_{\text{Individual Intercept}} + \beta x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\]

- \(\alpha_i\) is the Fixed Effect. It captures EVERYTHING that is:

- Specific to individual \(i\)

- Constant over time (time-invariant)

- Even if we can’t observe it! (e.g., “Culture”, “Talent”)

Fixed effect (implementation)

- Fixed effect regression: \[ y_{i,t} = a + a_i + b x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\] is equivalent to \[ y_{i,t} = a.1 + a_1 d_{i=1} + \cdots + a_I d_{i=I} + b x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\] where \(d\) is a dummy variable such that \(d_{i=j} = \begin{cases}1, & \text{if}\ i=j \\\\ 0, & \text{otherwise}\end{cases}\)

- Minor problem: \(1, d_{i=1}, ... d_{i=I}\) are not independent: \(\sum_{j=1}^I \delta_{i=j}=1\)

- Solution: ignore one of them, exactly like the dummies for categorical variables

- Now the regression can be estimated with OLS…

Estimation methods

- … Now the regression can be estimated with OLS (or other)

- naive approach fails for big panels (lots of dummy regressors makes \(X^{\prime}X\) hard to invert)

- smart approach decomposes computation in several steps

- “between” and “within” estimator (for advanced panel course)

- software does it for us…

- Like always, we get estimates and significance numbers / confidence intervals

Time Fixed Effects

- Sometimes, we know the whole dataset is affected by common time-varying shocks

- assume there isn’t a variable we can use to capture them (unobservable shocks)

- We can use time-fixed effects to capture them: \[ y_{i,t} = a + a_t + b x_{i,t}\]

- Analysis is very similar to individual fixed effects

Both Fixed Effects

- We can capture time heterogeneity and individual heterogeneity at the same time. \[ y_{i,t} = a + a_i + a_t + b x_{i,t}\]

- More of it soon.

Limitation of fixed effects

- Problem with fixed effect model:

- each individual has a unique fixed effect

- it is impossible to predict it from other characteristics

- … and to compare an individual’s fixed effect to the predicted value

- Solution:

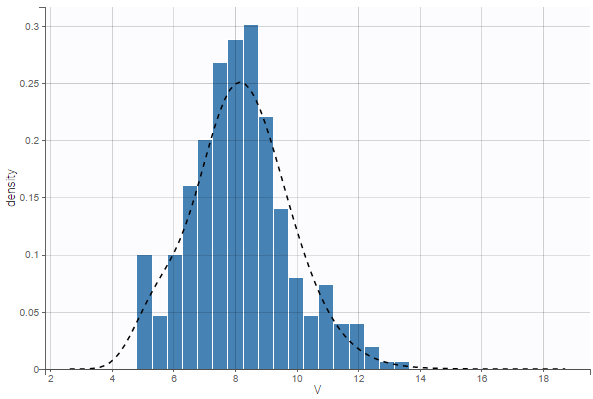

- instead of assuming that specific effect is completely free, constrain it to follow a distribution: \[y_{i,t} = \alpha + \beta x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\] \[\epsilon_{i,t} = \epsilon_i + \epsilon_t + \epsilon\]

- where \(\epsilon_{i}\), \(\epsilon_t\) and \(\epsilon\) are random variables with usual normality assumptions

Other models

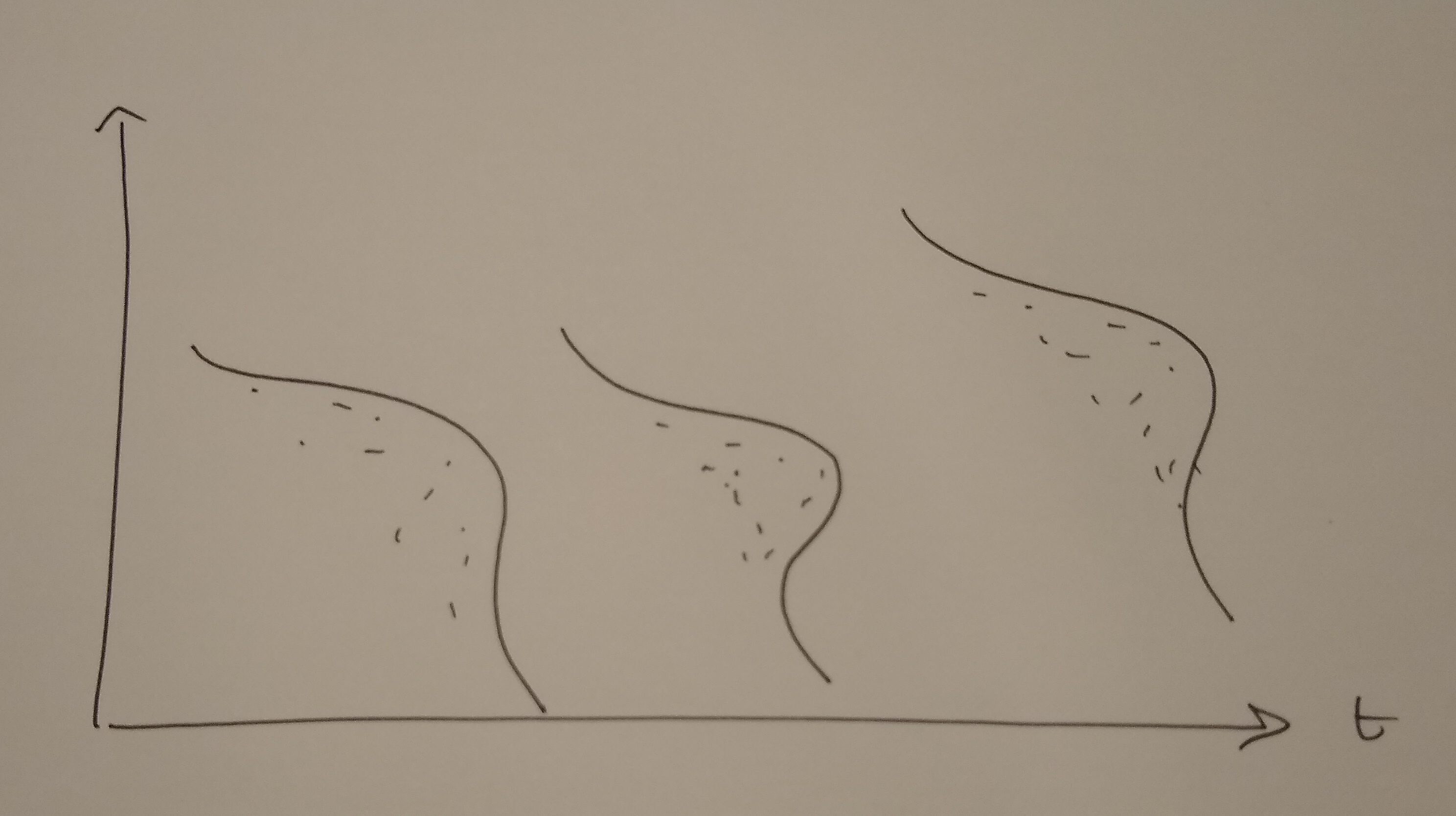

Composed coefficients: (coefficients can also be heterogenous in both dimension)

\[y_{i,t} = \alpha_i + \alpha_t + (\beta_i + \beta_t) x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\]

Random coefficients …

Diff in Diff

A Quasi-Experiment

The Setup

- Scenario: A school introduces a tutoring program.

- Problem: Usually, students who need help sign up.

- Comparing Tutors vs Non-Tutors is biased (selection bias).

- The Diff-in-Diff Trick:

- Don’t compare levels. Compare changes.

- Compare the improvement of tutored students vs the improvement of non-tutored students.

Formalization

- Two groups: Treated (\(T=1\)) and Control (\(T=0\)).

- Two periods: Pre (\(t=0\)) and Post (\(t=1\)).

- Goal: Isolate the effect of the Treatment.

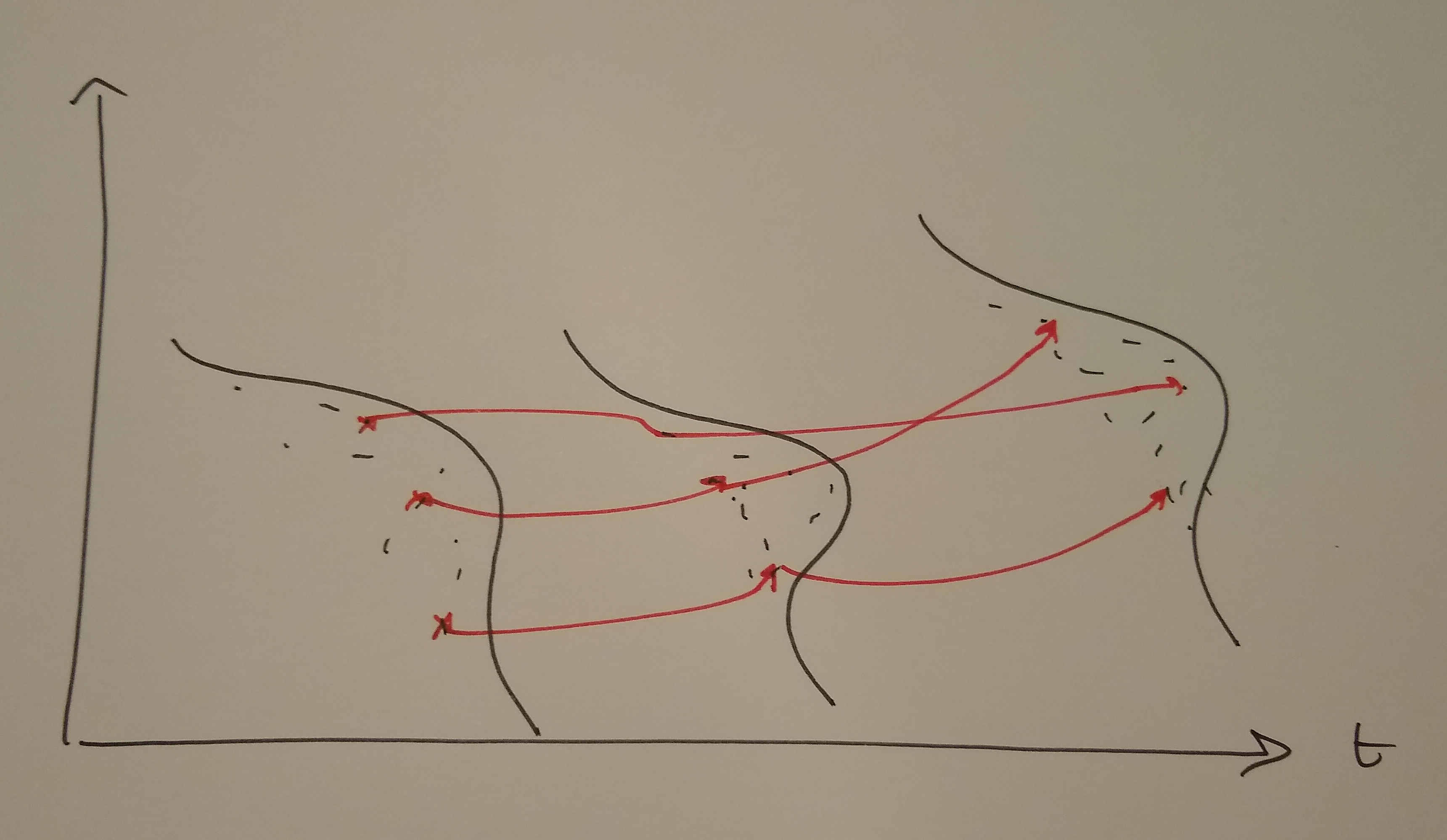

Graphical Intuition

The Logic of Diff-in-Diff

- Goal: Estimate the extra growth of the treated group compared to the control group.

\[ \text{DID} = (\bar{y}_{\text{Treat}, \text{Post}} - \bar{y}_{\text{Treat}, \text{Pre}}) - (\bar{y}_{\text{Control}, \text{Post}} - \bar{y}_{\text{Control}, \text{Pre}}) \]

- Interpretation:

- \((\bar{y}_{C,\text{Post}} - \bar{y}_{C,\text{Pre}})\): The “Normal” time trend (what would have happened anyway).

- \((\bar{y}_{T,\text{Post}} - \bar{y}_{T,\text{Pre}})\): The actual change for the Treated.

- The difference is the Causal Effect.

- Key Assumption: Parallel Trends.

- Without treatment, both groups would have followed the same trend.

Implementing Diff-in-Diff

We estimate it using a regression with an Interaction Term:

\[y_{i,t} = \alpha + \beta_1 \underbrace{\text{Treat}_i}_{\text{Group}} + \beta_2 \underbrace{\text{Post}_t}_{\text{Time}} + \delta (\underbrace{\text{Treat}_i \times \text{Post}_t}_{\text{Interaction}}) + \epsilon_{i,t}\]

- \(\beta_1\): Baseline difference between groups.

- \(\beta_2\): Common time trend.

- \(\delta\): The Difference-in-Differences estimator.

\(\delta\) captures the extra jump that the treated group experiences in the second period. This is our causal effect!

Generalized Diff-in-Diff

Scenario:

- Multiple time periods.

- Different individuals get treated at different times (Staggered adoption).

The Model: Two-Way Fixed Effects (TWFE) \[y_{i,t} = \underbrace{\alpha_{i}}_{\text{Entity FE}} + \underbrace{\alpha_t}_{\text{Time FE}} + \delta D_{i,t} + \beta x_{i,t} + \epsilon_{i,t}\]

\(D_{i,t}\): The “Post-Treatment” dummy

- \(D_{i,t} = 1\) if individual \(i\) is actively treated at time \(t\).

- \(D_{i,t} = 0\) otherwise.

Conclusion: This is the standard workhorse model for policy evaluation in economics.

In practice: Python

Using the

linearmodelslibrary (built on top of pandas/statsmodels).Entity Fixed Effects:

from linearmodels import PanelOLS # ... load data ... mod = PanelOLS.from_formula('invest ~ 1 + value + capital + EntityEffects', data=df) res = mod.fit()Two-Way Fixed Effects:

mod = PanelOLS.from_formula('invest ~ 1 + value + capital + EntityEffects + TimeEffects', data=df) res = mod.fit()

PanelOLS handles the dummy variable math efficiently. Don’t try to create 1000 columns of dummies yourself!

Conclusion

Takeaways

- More Data, More Power: Panel data combines the best of cross-sections (“differences between people”) and time-series (“changes over time”).

- Control the Unobservable:

- For simple cases, you can just add dummy variables to control for heterogeneity, or do different regressions for different groups

- Use Fixed Effects to absorb constant individual characteristics (culture, ability) that would otherwise bias your results.

- Think Causally: Diff-in-Diff allows for powerful quasi-experimental analysis (Treated vs Control, Before vs After).

- Tools: Use

linearmodelsin Python to handle the complexity automatically.