Intro to Heterogeneity

Macro II - Fluctuations - ENSAE, 2024-2025

2025-03-26

Heterogeneity in models

DSGE models are often criticized for unrealistic assumptions

Example:

Macroeconomic Policy in DSGE and Agent-Based Models from Revue de l’OFCE

In that respect, the Great Recessions has revealed to be a natural experiment for economic analysis, showing the inadequacy of the predominant theoretical frameworks. Indeed, an increasing number of leading economists claim that the current ’’economic crisis is a crisis for economic theory’’ (Kirman, 2010; Colander et al., 2009; Krugman, 2009, 2011; Caballero, 2010; Stiglitz, 2011; Kay, 2011; Dosi, 2011; Delong, 2011). The basic assumptions of mainstream DSGE models, e.g. rational expectations, representative agents, perfect markets etc., prevent the understanding of basic phenomena underlying the current economic crisis

But:

mainstream models typically incorporate many non classical elements. For instance New Keynesian models feature imperfect competition

one must distinguish mainstream models from DSGE methodology

- today: DSGE model with rather radical conclusion

Representative Agent

Under the Representative agent assumption

- aggregate choices are made as the result of a single optimization problem

- ☡ there might restrictions on what is internalized by the agent

Is it a simplifying assumption?

Or is it actually equivalent to the aggregation of many optimization problems?

For the latter one needs a theory of aggregation1

- … which quickly breaks down (for instance when utility fonction are heterogenous)

Example with the Neoclassical Model

Let’s consider three versions of the neoclassical model

- fully decentralized (many firms, many consumers)

- representative agent

- planner problem

Note:

- for the neoclassical model, there is a theory of aggregation for the production sector (firms are Cobb-Douglas)

- two assumptions are needed to aggregate consumers: log-utility and no uncertainty

Heterogenous Agents

Some economists have recognized early the need to explicitly model heterogeneity.

1977: Bewley

- idiosyncratic stochastic endowment

- consumption-savings model with borrowing constraints

- leads to ex-post heterogeneity (constrained/unconstrained) hence different reactions

Huggett Economy (1993)

- additional ex-ante heterogeneity in idiosyncratic income process

Ayiagari Model (1994)

- savings are invested to accumulate aggregate capital

- consumption-savings model with borrowing constraints

- idiosyncratic productivity shocks (salary)

Krussell Smith Model (1998)

- Ayagari + aggregate shocks

Those models require special computational techniques and were poorly understood mathematically

Mean Field Games and Heterogenous Agents Models

2012 Ben Moll did a talk at IMA (UK)

Economists and world class mathematicians exchanged on mean field games

- a class of mathematical problems which encompasses heterogenous agents models

- a bit math intense (stochastic calculus, viscosity theory, …)

Mean Field Games and Heterogenous Agents Models

2012 Ben Moll did a talk at IMA (UK)

Result: a new stream of heterogenous agents papers

PDE Models in Macroeconomics (2014) with Achdou, Bueary, Lasry, Lions

The Dynamics of Inequality (2016) with Gabaix, Lasry, Lions

Monetary Policy According to HANK (2018) with Kaplan and Violante

- that one was hugely successfull

HANK, HANK HANK, …

Monetary Policy According to HANK (2018), by Moll, Kaplan and Violante

- HANK: Heterogenous Agents New Keynesian

- study unequal consequences of monetary policies

- a new baseline model for central banks

Stimulated a whole literature1

- Understanding HANK: Insights from a PRANK2

- When HANK meets SAM

- HANK beyond FIRE

- Aggregate Demand: THANK (Tractable HANK) and TANK by Florin Bilbiie

- main point: you don’t need more than two agents to get the main insights

Heterogenous consumers

Why does it matter to model consumer’s heterogeneity?

- To reproduce realistic consumption decisions.

Classically, we make the difference between two kinds of agents:

Ricardian Households

Agents who can freely reallocate consumption intertemporally.

They have a high marginal propensity to consume out of additional income.

Ricardian households choose not to consume more today, in order to consume more tomorrow.

Keynesian Households

Agents whose consumption in the current period is limited by a binding credit constraint. Either they can’t borrow at all or the amount they can borrow is limited today.

They have a high marginal propensity to consume out of additional income.

Keynesian Households consume today as much as they can.

The representative agent assumes everyone is ricardian.

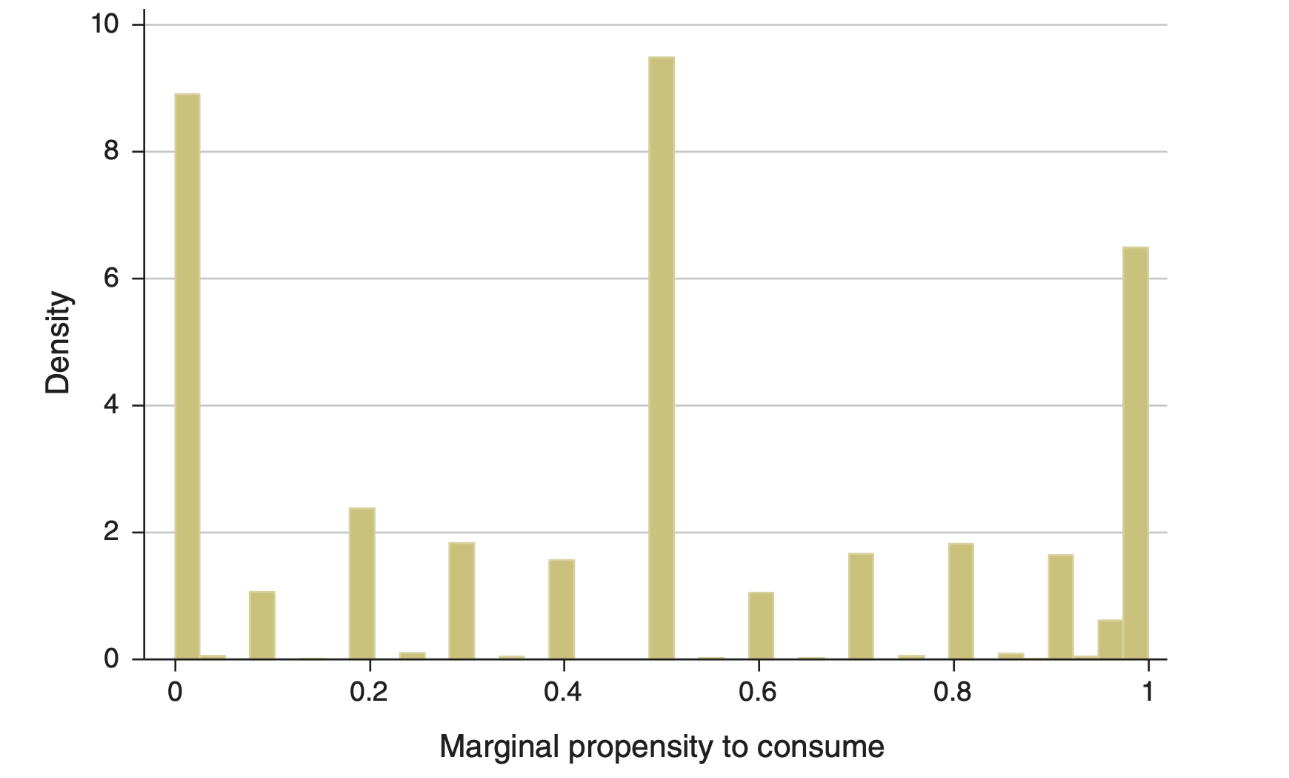

What does the data say?

Let’s have a look at the MPC distribution for France.1

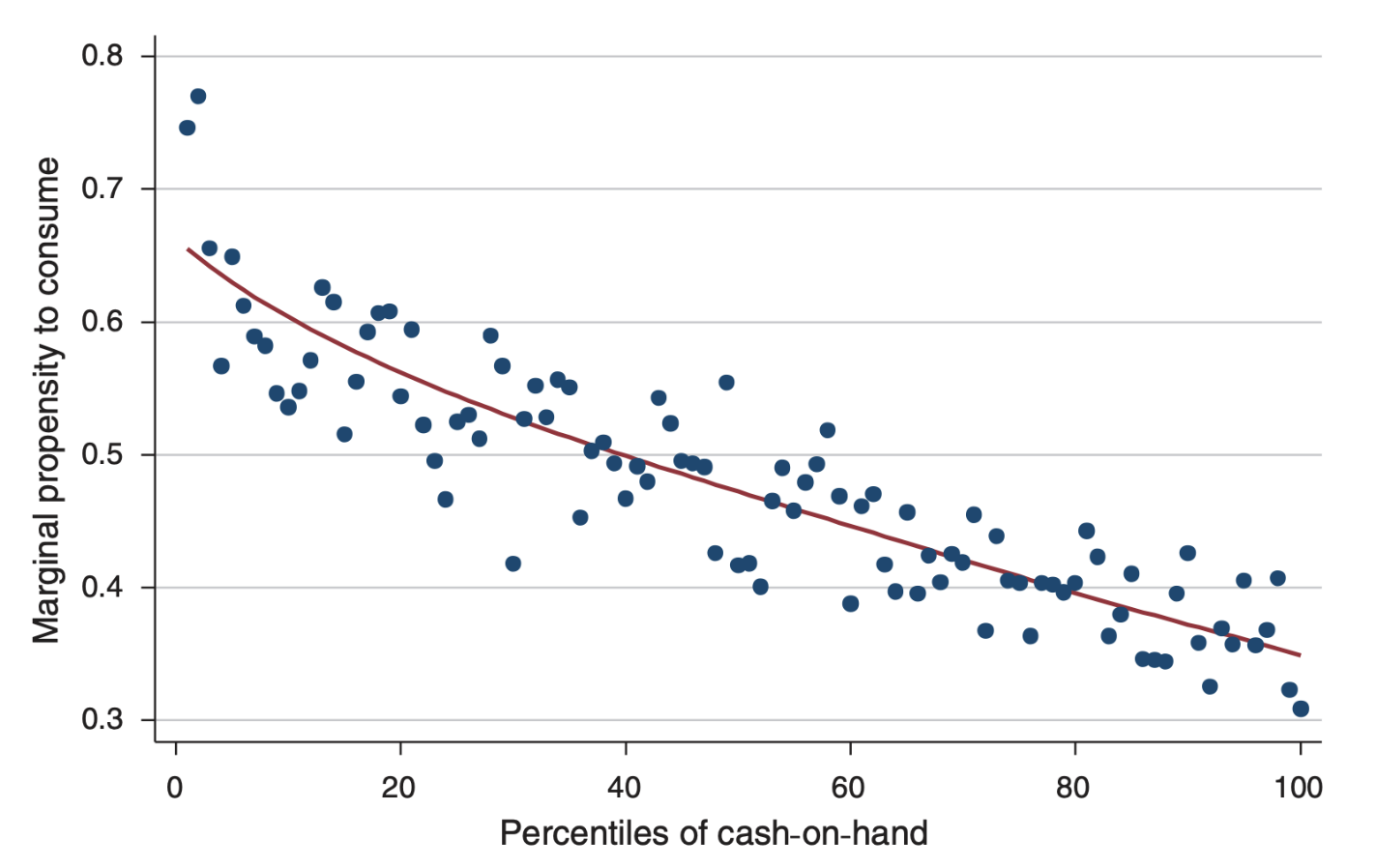

Average MPC by Cash-on-Hand Percentiles

Apparently MPC is well predicted by Cash-in-hand (amount of money left to household after having made all compulsory payments).

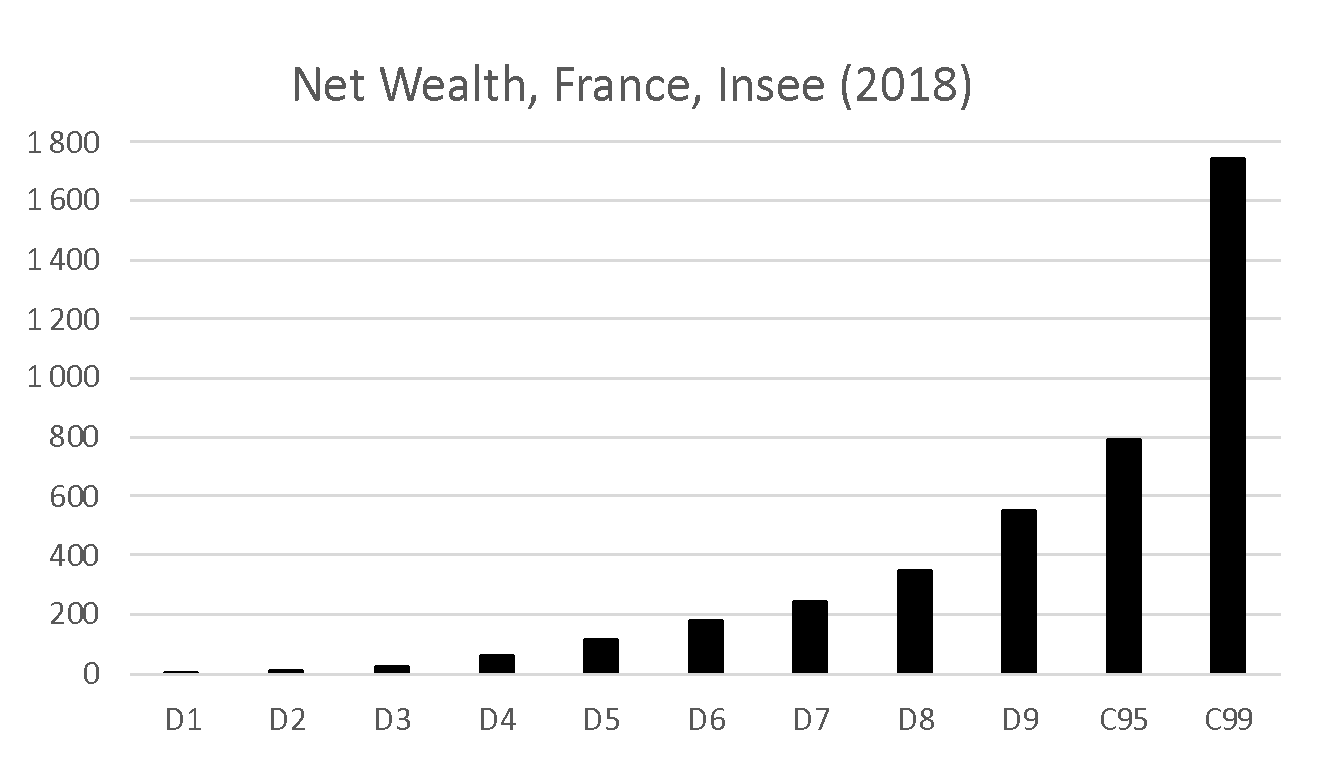

Wealth distribution

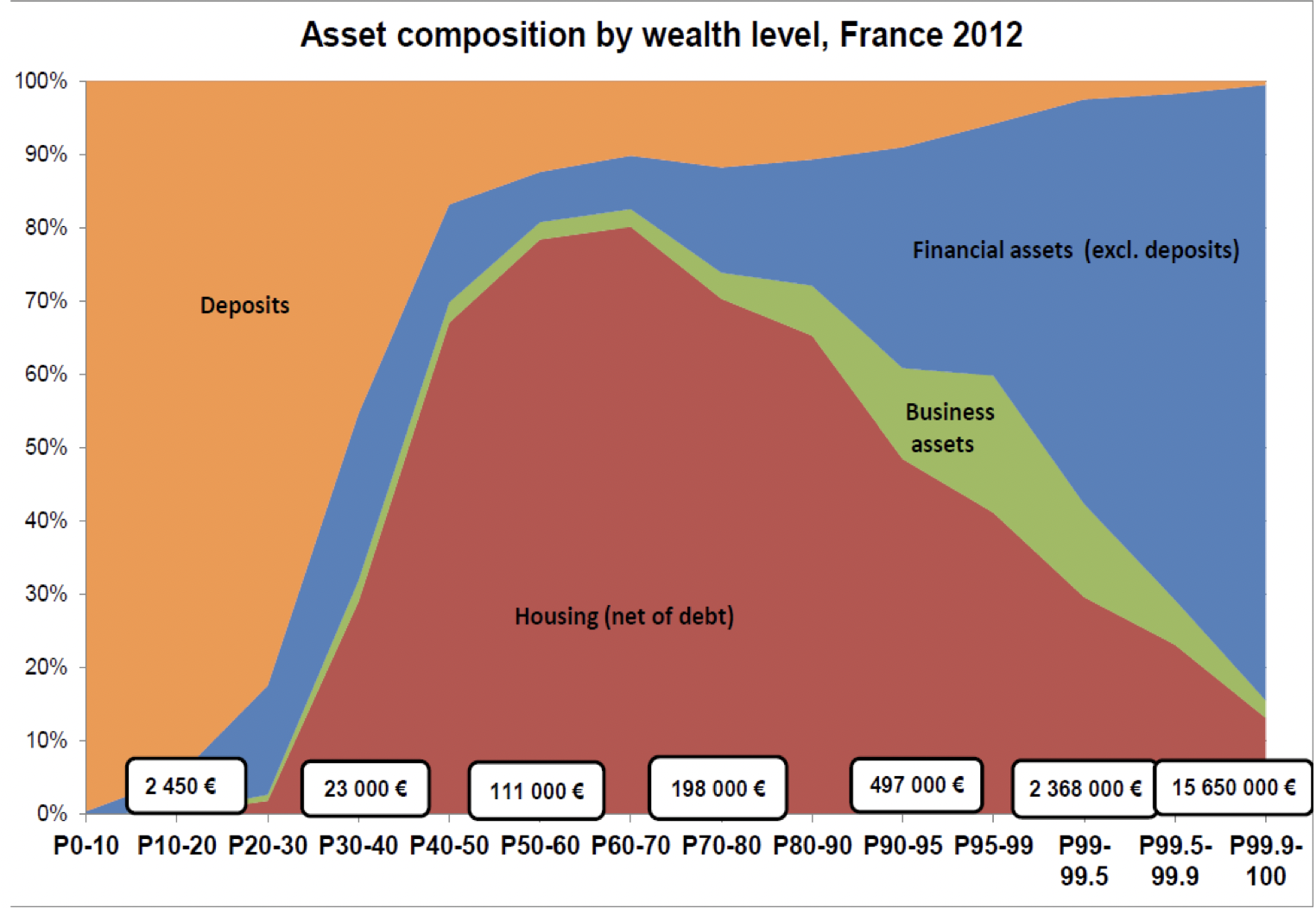

Wealth decomposition

Agents in the middle of the wealth distribution have a mortgage, whose interests leaves very little to spend after payments. They have lower cash-in-hand hence higher marginal propensity to consume (than rich agents).

Wealthy Hand to Mouth agents

We have just seen that agents in the middle of the wealth distribution, hold a wider proportion of wealth in illiquid assets (housing)

- Their cash in hand (available for immediate purchase) is reduced. A sizable fraction of ther income goes into repaying their loan…).

- They have higher MPC

- They also react to interest rates changes (notably those who have floating interest rates)

- “Monetary Policy According to HANK”, 2018, Kaplan, Moll and Violante, stress out the role of “wealthy hand to mouth” and the need to take their existence to evaluate the influence of monetary policies.

How do we model differences in MPC?

Specify several kinds of agents:

- ricardians

- hand to mouth (consumption = income)

- ex-ante heterogeneity

By endogenizing borrowing constraint with borrowing constraint

- requires nonlinear solution

- ex-post heterogeneity

- with potential idiosyncratic parameters like time-discount (ex-ante heterogeneity)

By using preference for wealth

- coming next

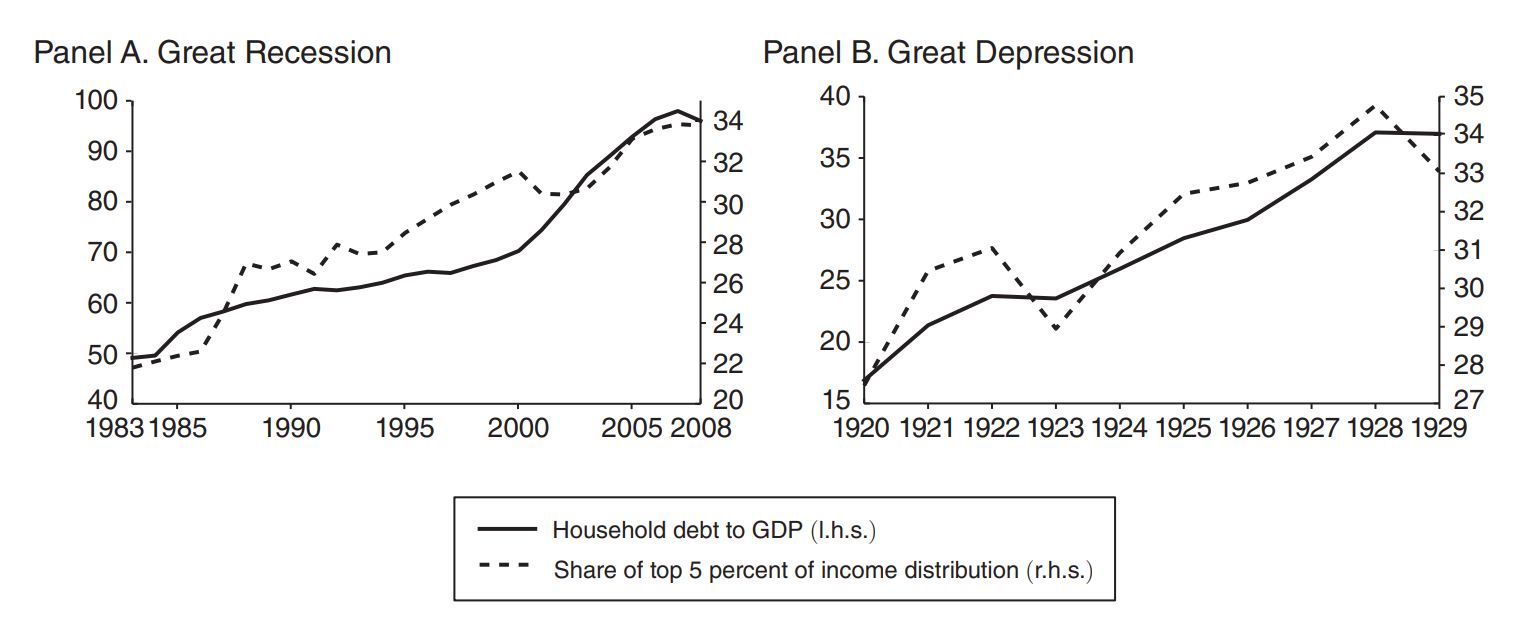

Inequality, Leverage and Crisis

Inequality, Leverage and Crisis, Kumhof, Rancière, Winant (2015)

Introduction

The 2007 financial crisis, was initially as subprime mortgage crisis

- high indebtedness from low income households

- fueled by easy credit (low i.r.) and high house prices

- debt-securitization

- even for high risk debt (subprimes)

- of which 90% had variable interest rates and/or balloon payments

- (moderate) rise in interest rates

- bursting of the housing buble

- households were unable to refinance their loans

- … and defaulted

- mbs market collapsed…

- … and with it the whole financial sector

Ok, but from a macro perspective, what fueled such high levels of borrowing?

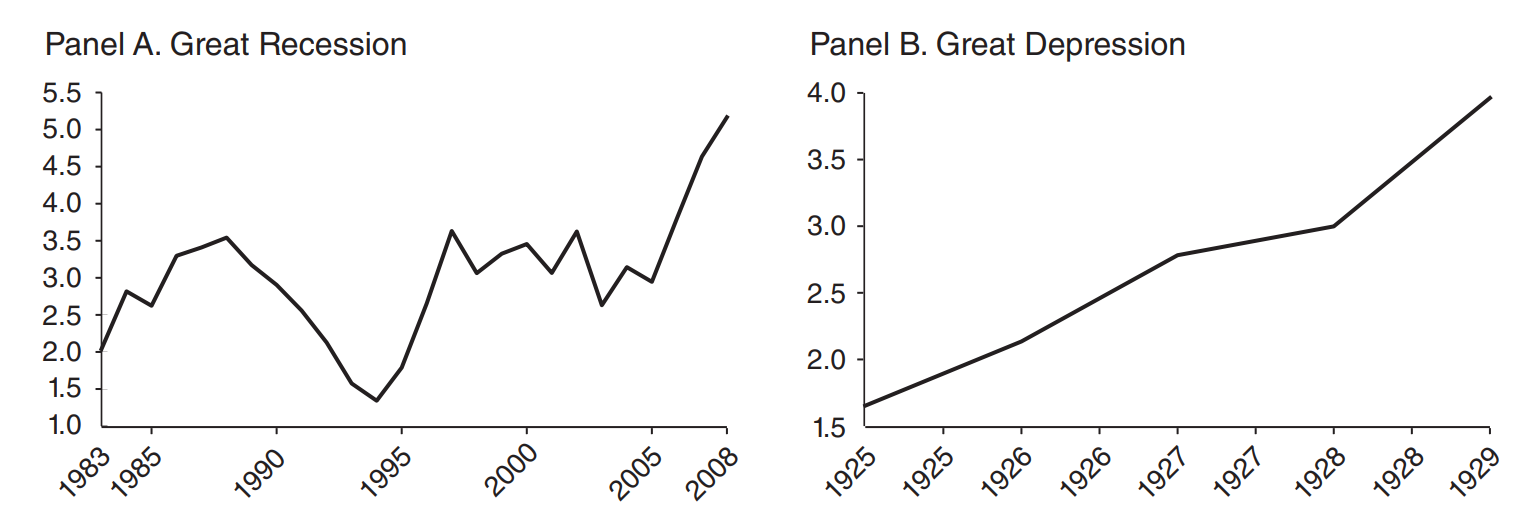

A similar pattern emerged before the great recession and before the great depression:1

- parallel increases in income inequality and debt over income ratios

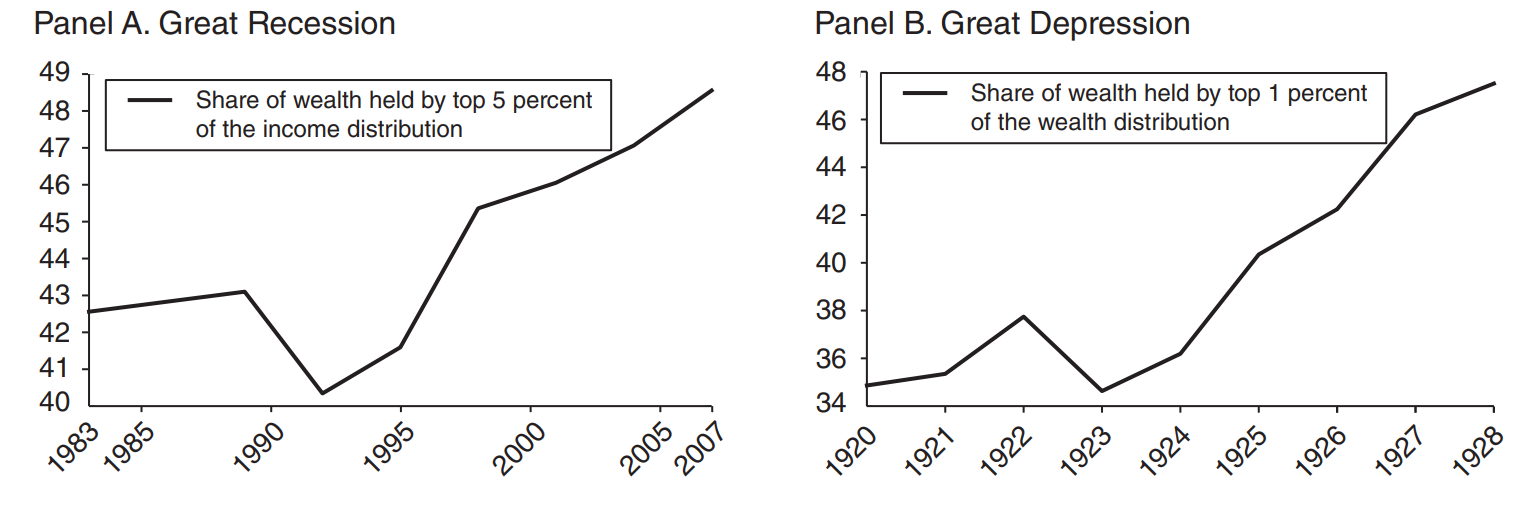

Wealth Inequality

Increase in wealth inequality is consistent.

Econometric measures of household default risk 1 rose consistently.

Model

What could link rising income inequality to increased borrowing by bottom-earners?

Intuition:

- top-earners have higher marginal propensity to save

- when their income increases they lend to bottom earners

- and rising debt increases the risk of default

Let’s see how to model that in DSGE fashion (ommiting default risk for the sake of simplicity)

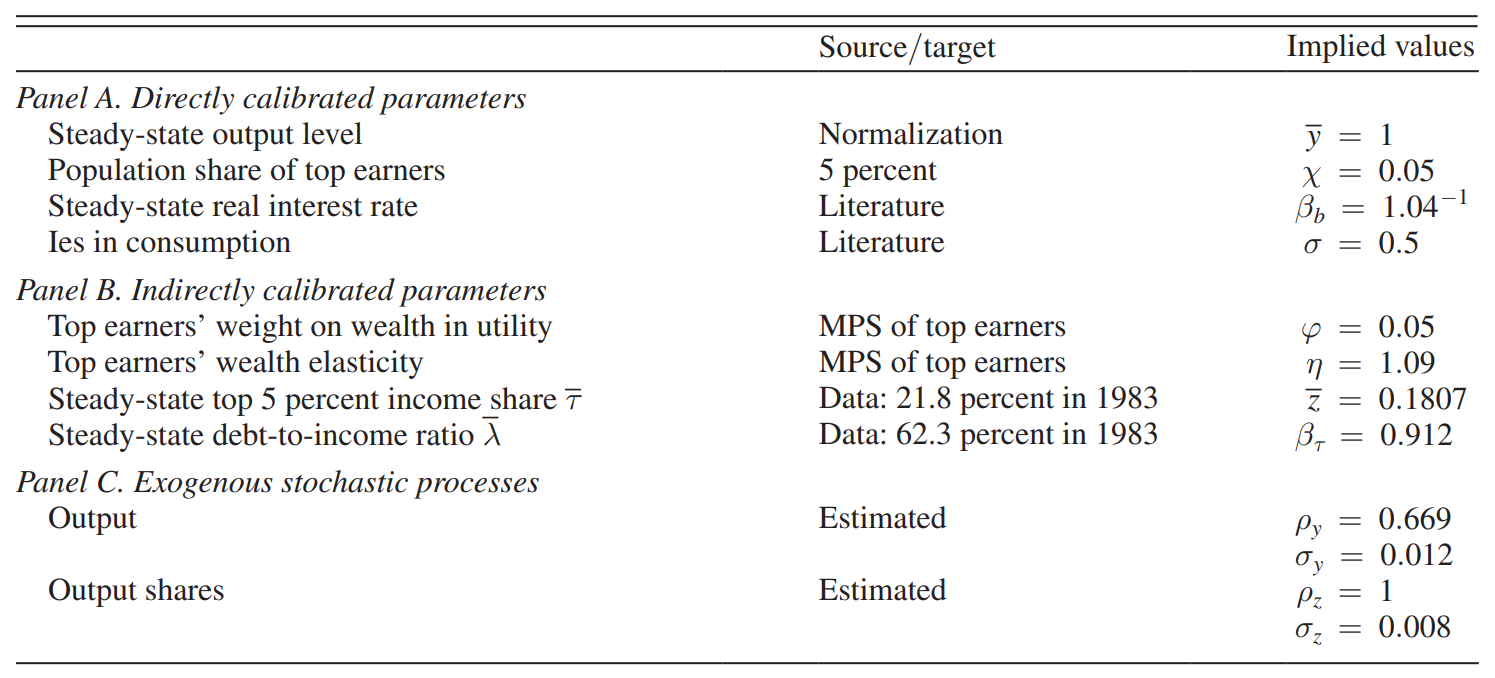

Endowments

We consider and endowment economy:

- Total output

\[y_t = (1-\rho_y) \overline{y} + \rho_y y_{t-1} + \epsilon_{y,t}\]

- Inequality shock

\[z_t = (1-\rho_z) \overline{z} + \rho_z z_{t-1} + \epsilon_{z,t}\]

Comments:

\(z_t\) is the fraction of the total output that is received by top-earners. The rest is received by bottom earners.

We assume there is a faction \(\chi\) of top earners.

our goal is to study the effect of a persistent inequality shock (with \(\rho_z=1\))

- we need a way to model nonzero marginal propensity to save out of a persistent income shock

Top Earners

We choose the following utility function for top earners: \[U_t = E_t \sum_{k\geq0}^{\infty} \beta^k_{\tau} \left\{ \frac{\left(c^{\tau}_{t+k}\right)^ {1-\frac{1}{\sigma}}}{1-\frac{1}{\sigma}} + \varphi \frac{\left( 1+b_{t+k}\frac{1-\chi}{\chi}\right)^{1-\frac{1}{\eta}}}{1-\frac{1}{\eta}} \right\}\]

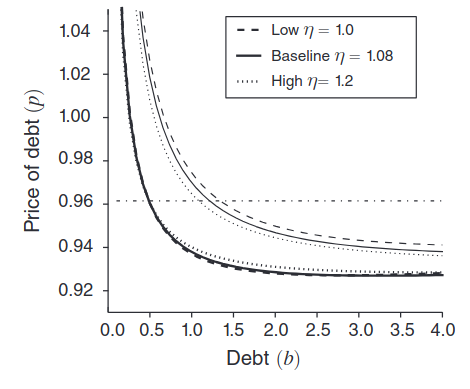

Consumption: \[c^{\tau}_t = y_t z_t \frac{1}{\chi} + \left(b_{t-1}-b_t p_t\right)\frac{1-\chi}{\chi}\] where \(b_t\) is debt holdings and \(p_t\) the price of it \(1/r_t\)

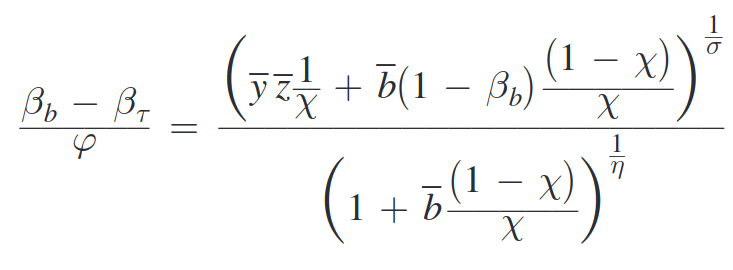

Optimality condition from \(\max U_t\)

\[p_t = \beta_{\tau} E_t\left[ \left( \frac{c^{\tau}_{t+1}}{c^{\tau}_t}\right)^ {-\frac{1}{\sigma}}\right] + \varphi \frac{\left(1+b_t \frac{1-\chi}{\chi}\right)^ {-\frac{1}{\eta}}}{\left(c_t^{\tau}\right)^ {-\frac{1}{\sigma}}}\]

Preference for Wealth

The preference for wealth can be justified as:

- a preference for social status

- capitalist spirit

It implies a steady-state supply of lending for any income level:

Which in turn implies non-zero marginal propensity to save from a permanent income shock (in the short and the long run)

Parameters \(\eta\) and \(\varphi\) are not observed, but can be chosen in order to match real world MPC (50% for top earners).

Bottom Earners

Bottom earners are standard:

\[V_t = E_t \sum_{k \geq 0}^{\infty} \beta^k_b \left( \frac{\left(c_{t+k}^b\right)^ {1-\frac{1}{\sigma}}}{1-\frac{1}{\sigma}} \right)\]

Budget constraint:

\[c^b_t = y_t(1-z_t)\frac{1}{1-\chi} + \left(b_t p_t - b_{t-1}\right)\]

Optimality condition from \(\max V_t\)

\[p_t = \beta^b E_t \left[ \left( \frac{c_{t+1}^b}{c_t^b}\right)^{-\frac{1}{\sigma}} \right]\]

Calibration

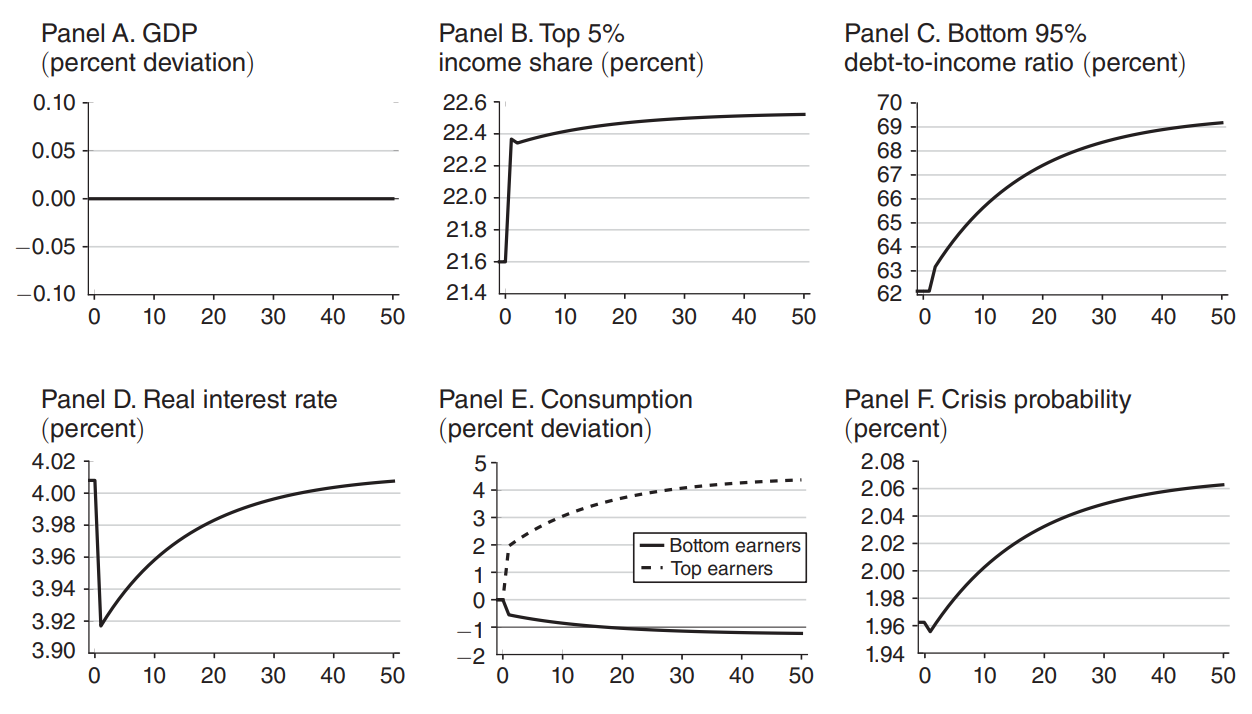

Inequality Shock

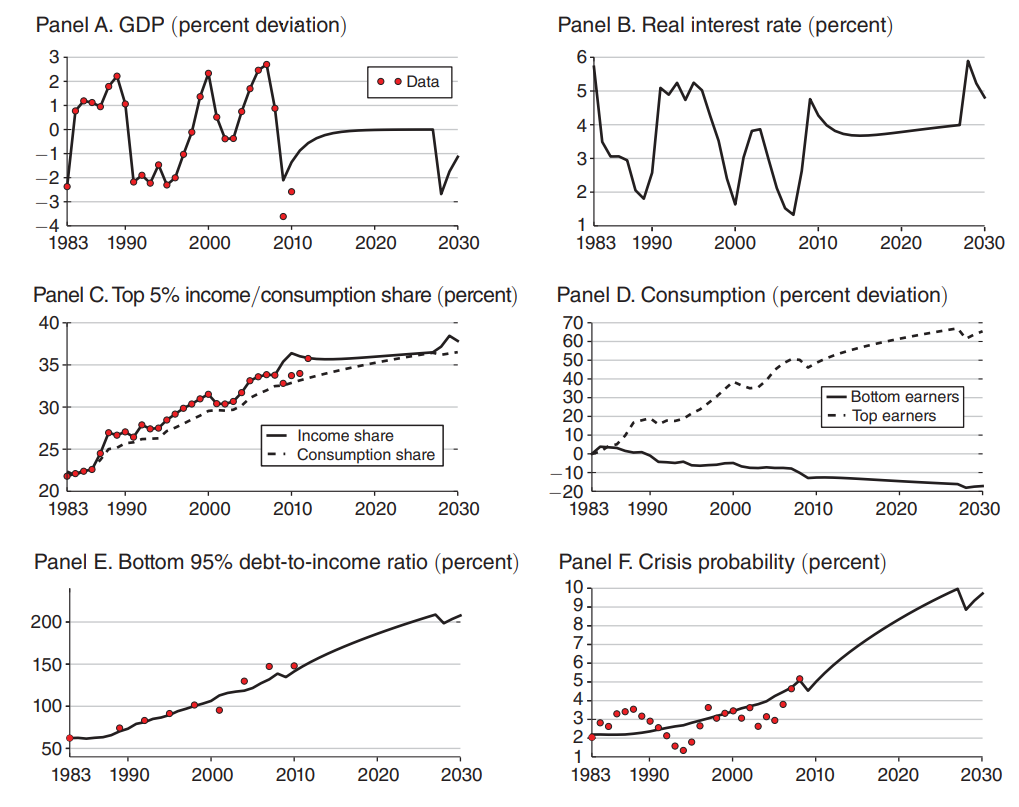

Pseudo-Historical Simulation

In the simulation we use historical values for the driving shocks (output and inequality).

What is the predictive power of the model:

- we match one moment: the evolution of debt/gdep from 1983 to 2010