The Rise of Artificial Intelligence

Topics in Economics, ESCP, 2025-2026

Introduction

Will only appear in HTML.

How do you see the future of AI ?

. . .

. . .

- Science Fiction has explored many issues associated with AI.

- what happens to individuals, markets, firms, government?

- who wins, who loses?

- Very often economic future is bleak…

- Why is that so?

What is AI?

A simple definition (enough for this course)

AI is a set of methods that learns from data to produce useful outputs (predictions, classifications, text/images, actions).

- Key idea: it improves with experience/training, not just explicit rules

- We do not need AI to “think like a human” for it to matter economically

Why it is hard to say what AI will never do

Two recurring facts:

- The frontier moves: tasks once seen as “uniquely human” become routine (translation, chess, image recognition, writing)

- Our labels move too: once a task is solved reliably, we stop calling it “AI”

- (Tesler’s theorem / “AI is whatever hasn’t been done yet”)

. . .

So claims like “AI will never do X” usually age badly.

What we can be more confident about

Even if we cannot bound capabilities, we can analyze economic mechanisms:

- which tasks become cheaper (prediction, drafting, search, monitoring)

- which inputs become valuable (data, compute, human attention)

- who captures rents (owners of complements and bottlenecks)

The Classical View

“This Time it’s Different” or “Same old, same old…”?

. . .

Do you remember the neoclassical production function?

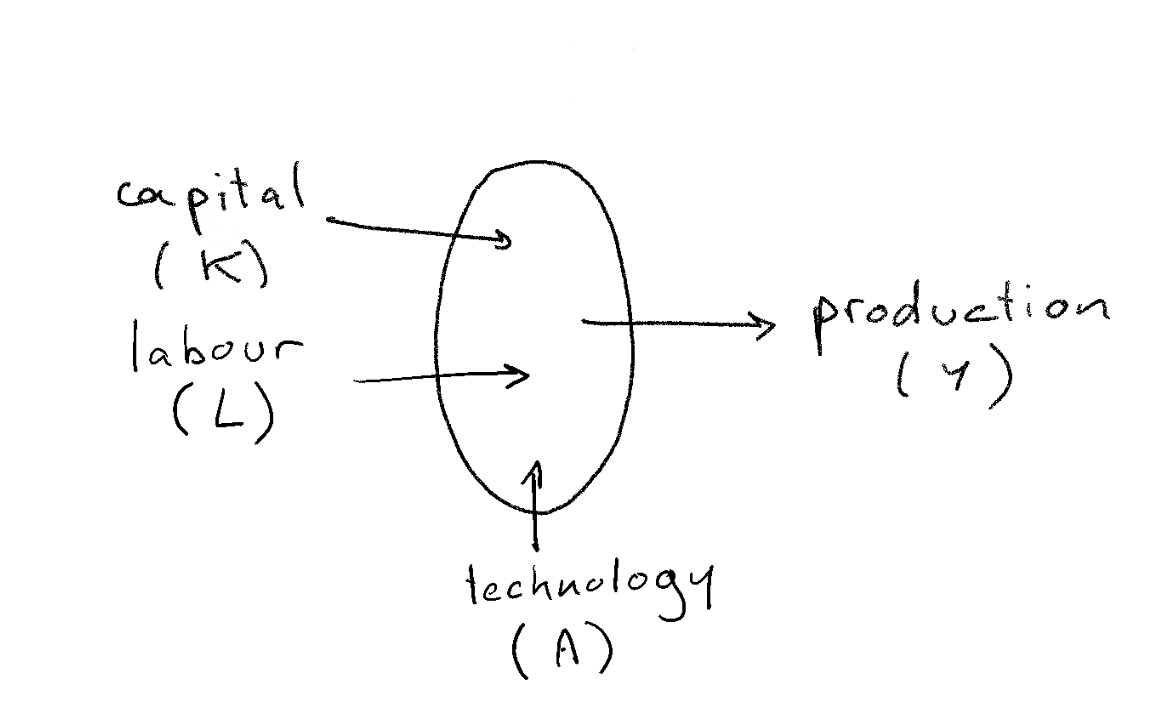

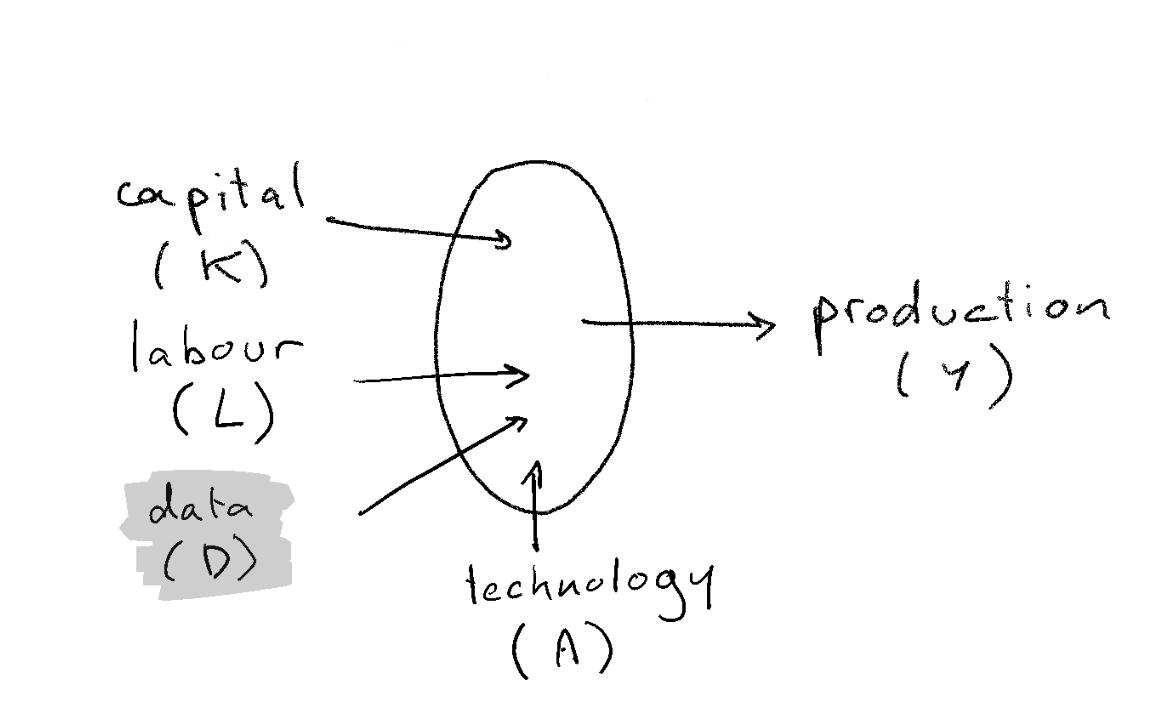

The (neo)classical production function

What are its main properties?

- production takes several factors as inputs

- capital

- labour

- … (natural resources, land, …)

- each factor has a market price

- marginal returns w.r.t. each factor are decreasing

- factors are paid according to their marginal productivity

- the technology is the particular process through which inputs are combined

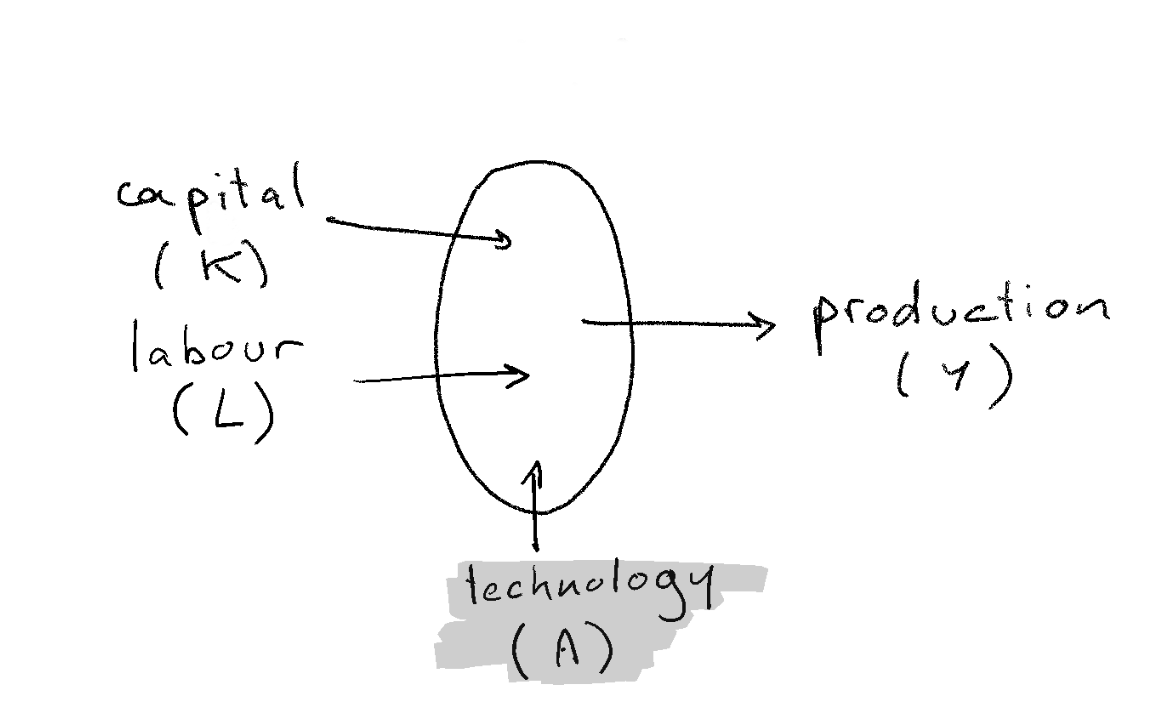

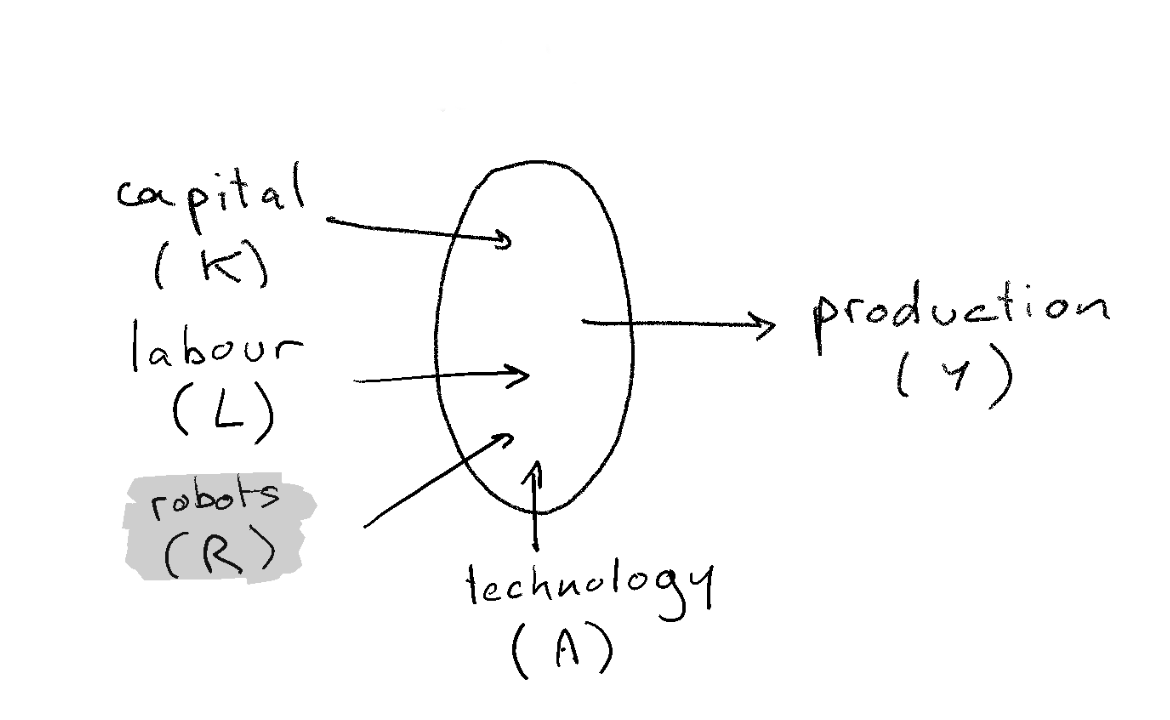

AI and the (neo)classical production function

- the precise description depends on the problem under consideration

- what could you change to take into account the effect of AI?

- data, technological change ?

Three hypotheses about the economic nature of AI

- A technological change

- A new kind of factor: Data

- Yet another kind of factor: Robots

- Something else Completely

AI is a change in the cost structure

Ajy Agrawal, Joshua Gans and Avi Goldfarb: Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence 2018

Prediction Machines

- many production tasks can be formulated as prediction problems

- examples:

- regression, classification: predict Y as a function of X

- student -> pass or fail ?

- should I invest in A or B ?

- even chatbot: what is the appropriate continuation for an ongoing conversation?

Will I lose my job ?

- AI is a decrease in the cost of predictions

- The demand for all prediction-intensive tasks will rise (law of demand)

- The salary of workers with prediction-intensive tasks will rise (market price)

- Value of other tasks will fall (general equilibrium effect)

- More precisely:

- demand for tasks that are substitute to predictions will be low

- demand for tasks that are complement to predictions will be high

A simple tasks-model framing (why employment effects are ambiguous)

- Jobs are bundles of tasks; AI rarely replaces entire occupations at once

- If AI substitutes for tasks you do, your marginal product may fall

- If AI complements tasks you do (e.g., better targeting, better diagnostics), your marginal product may rise

- Aggregate employment depends on substitution, new tasks/products, demand expansion, and reallocation frictions

- Distributional effects (who owns the complements/data/capital) are usually first-order

. . .

👉 More on it next week.

AI is Data

Chad Jones and Christopher Tonetti (Stanford) Nonrivalry and the Economics of Data (Sep 2020, American Economic Review)

Data is a factor not a technology

- Data is a factor, not a technology

- Can you explain it ?

- The difference between an idea and a factor? Examples:

- idea: use machine learning to build self driving cars

- factor: each car-maker gathering his own data to train cars

- Data (even anonymous) improves quality of existing products

What kind of good is data ?

- Remember the classification of goods?

- nonrival: can be used with leftovers

- excludable: use can be limited to paying customers

- data is a: club good

- Nonrivality implies

- increasing returns to scale

- 🤔: check why

- marginal value of new data increases more than proportionally

AI: adds data to the production function (consequences)

- increasing returns to scale implies natural monopoly

- ->GAFAMs

- increasing suboptimal monopoly rents (already a problem before existence of AI…)

- should you regulate a monopoly?

- it depends what is the barrier to entry: data-gathering or data-processing (cloud)

- other relevant questions

- where are the markets? (empirically seems to be “undertraded”)

- who owns the data ? Consumer, producer.

How do you regulate a Data-monopoly ?

- solutions:

- split the monopolies (if deadweight loss is too big)

- outlaw data gathering (big productivity loss)

- force data-sharing: make it a public good

- let the consumer be free to decide whether to rent their data (remove externalities)

AI: competition between humans and robots

Economic singularity

- In the very long run, could technology be bad?

- Recall the neoclassical world

- market economy

- technological progress reduces production cost

- always good for consumers. Increase (real) total income.

- becomes an inequality problem

- But

- whether technology reduces salaries depends on whether growth is labour augmenting or capital augmenting

- if AI is a close enough substitute for labour, salaries of “humans” as a whole are at risk

- there is an economic singularity when the wage of humans falls below the subsistence level

- Two sets of authors reach very similar conclusions

- Anton Korinek and Joseph Stiglitz (left): more complete/technical

- Gilles Saint Paul (right): more political economy

Some very long run scenarios

- Analysis taken from Gilles Saint Paul

- Main hypothesis: all humans can be replaced by more productive robots

- Comparative advantage logic:

- humans specialize in work where their comparative disadvantage is lowest (services, art, crafting…)

Scenario 1: society redistributes income from robots

Four political subscenarios:

Welfare state

- robot-owners are taxed, income is redistributed

- for instance as universal income

- some productivity losses

- what about international competitiveness?

Rentiers society

- robot owners invest the rent over many generations

- capital concentration increases

Neo-Fordism

- firms pay huge salaries for essentially useless jobs (powerpoint presentations, 😉 …)

- useful to sustain demand

New roman empire

- robot owners: patricians (top 2%)

- rest of population: plebeians

- survive thanks to clientelism

- robots: slaves

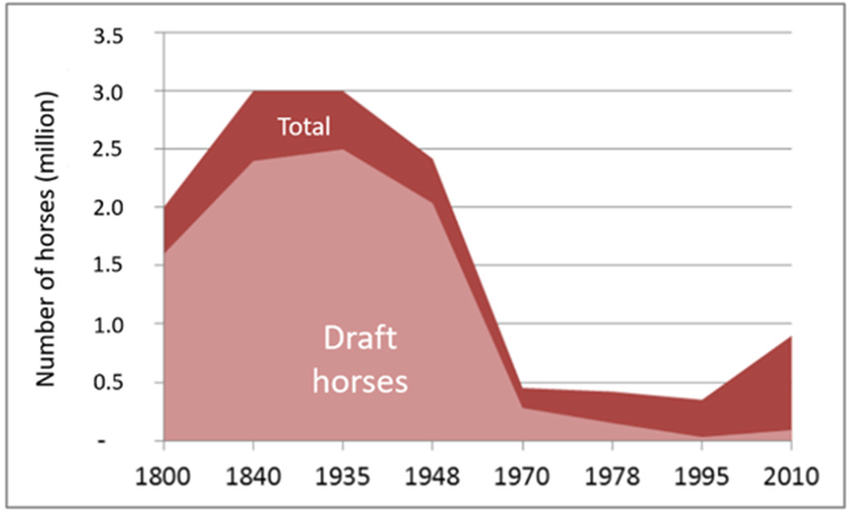

Scenario 2: wars, starvation, epidemic

- human income (marginal productivity) falls below subsistance levels

- malthusian effect: population growth decreases

- not unheard of (Leontief): consider population of draft horses

Scenario 3: the Matrix

- human wage decrease

- subsistence level decreases dramatically too

Something Else Completely?

- Right now AI is a technology (or a factor)

- What if it becomes another intelligent agent?

- has its own goals

- its own preferences

- with superhuman thinking abilities…

- Response in the literature (if curious):

- Anton Korinek: if market economy survives

- malthusian and non-malthusian scenarios

- At that stage humans might be something different completely

- transhumanism

- Anton Korinek: if market economy survives

Conclusion

- Research on AI is very speculative: especially about the long run

- But concepts from classical economics still help

- Very important assumption: “if market economy survives”

- For next time:

- make sure you understand all concepts in bold

More Readings

Chad Jones and Christopher Tonetti: Nonrivalry and the Economics of Data, American Economic Review

Avi GoldFarb: Prediction Machines: The Simple Economics of Artificial Intelligence 2018

Gilles Saint Paul: Robots Vers la fin du travail ?

Anton Korinek, Joseph E. Stiglitz: Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications for Income Distribution and Unemployment, chapter in Artificial Intelligence and Its Implications …, NBER

- also on coursera