| type | income | education | prestige | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rownames | ||||

| accountant | prof | 62 | 86 | 82 |

| pilot | prof | 72 | 76 | 83 |

| architect | prof | 75 | 92 | 90 |

| author | prof | 55 | 90 | 76 |

| chemist | prof | 64 | 86 | 90 |

Linear Regression

Data-Based Economics, ESCP, 2025-2026

2026-01-21

Descriptive Statistics

A Simple Dataset

Duncan’s Occupational Prestige Data

Many occupations in 1950.

Education and prestige associated to each occupation

\(x\): education

- Percentage of occupational incumbents in 1950 who were high school graduates

\(y\): income

- Percentage of occupational incumbents in the 1950 US Census who earned $3,500 or more per year

\(z\): Percentage of respondents in a social survey who rated the occupation as “good” or better in prestige

Quick look

Import the data from statsmodels’ dataset:

Descriptive Statistics

For any variable \(v\) with \(N\) observations:

- mean: \(\overline{v} = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N v_i\)

- variance \(V({v}) = \frac{1}{N} \sum_{i=1}^N \left(v_i - \overline{v} \right)^2\)

- standard deviation : \(\sigma(v)=\sqrt{V(v)}\)

| income | education | prestige | |

|---|---|---|---|

| count | 45.000000 | 45.000000 | 45.000000 |

| mean | 41.866667 | 52.555556 | 47.688889 |

| std | 24.435072 | 29.760831 | 31.510332 |

| min | 7.000000 | 7.000000 | 3.000000 |

| 25% | 21.000000 | 26.000000 | 16.000000 |

| 50% | 42.000000 | 45.000000 | 41.000000 |

| 75% | 64.000000 | 84.000000 | 81.000000 |

| max | 81.000000 | 100.000000 | 97.000000 |

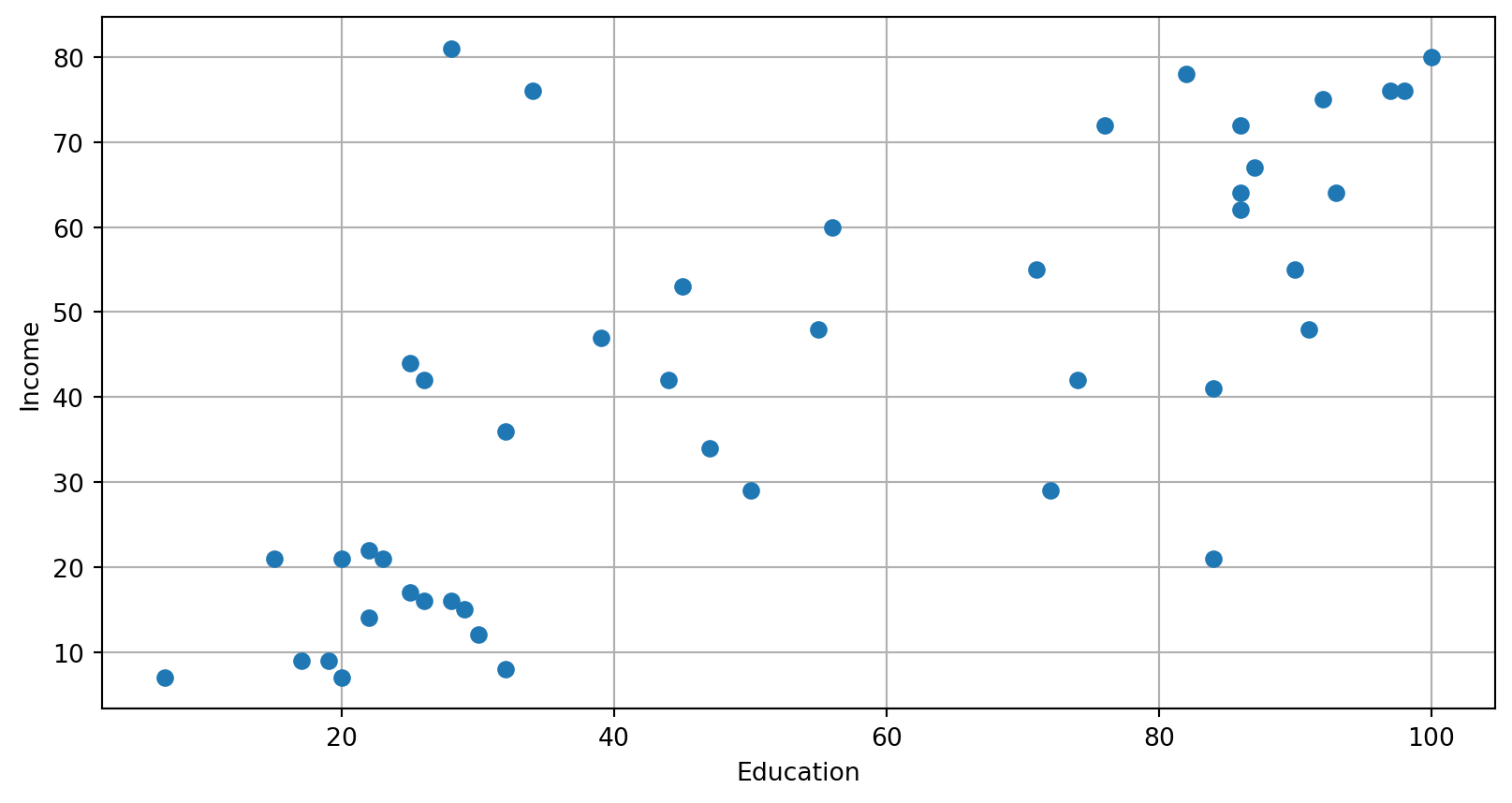

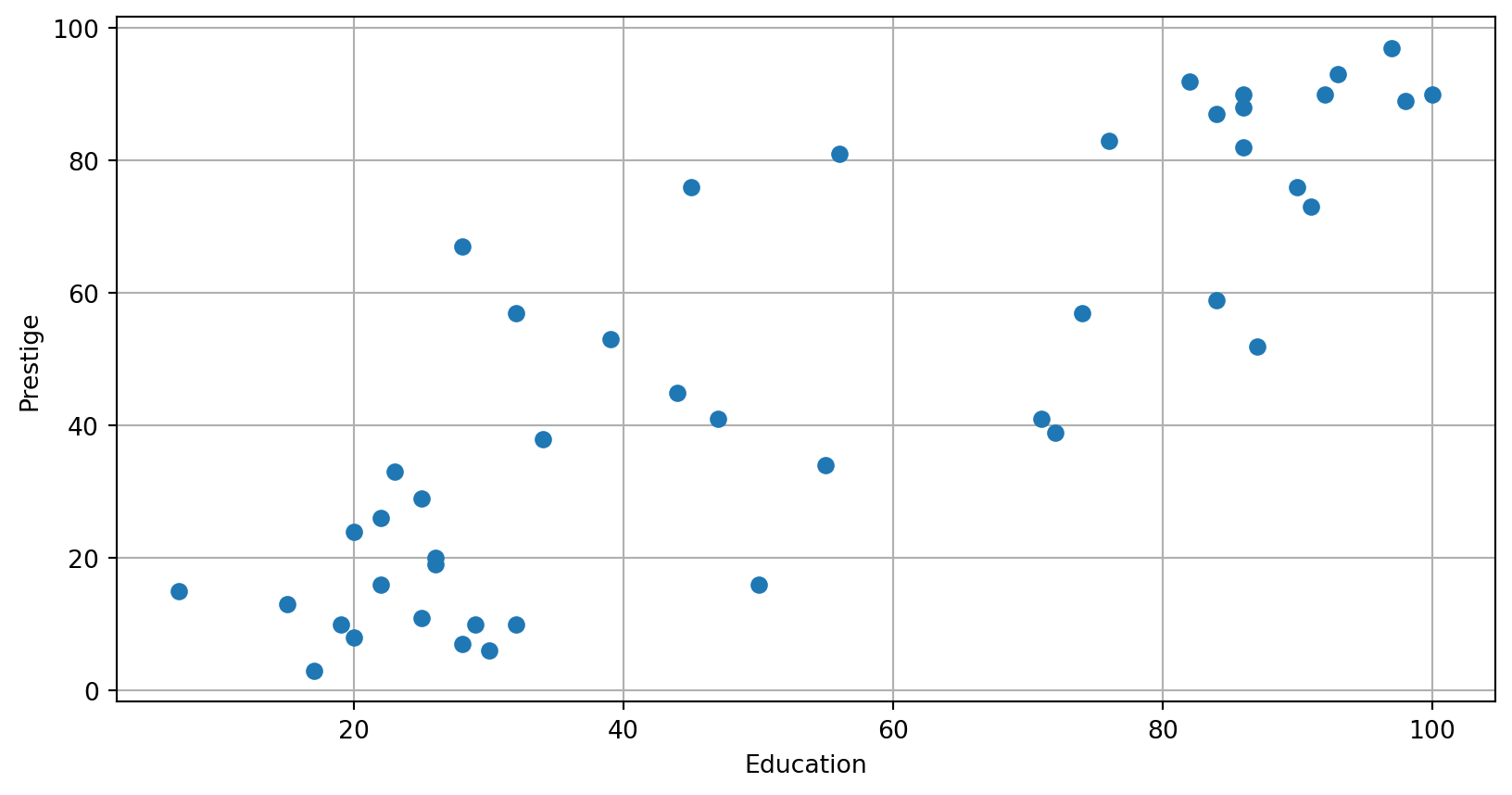

Relation between variables

- How do we measure relations between two variables (with \(N\) observations)

- Covariance: \(Cov(x,y) = \frac{1}{N}\sum_i (x_i-\overline{x})(y_i-\overline{y})\)

- Correlation: \(Cor(x,y) = \frac{Cov(x,y)}{\sigma(x)\sigma(y)}\)

- By construction, \(Cor(x,y)\in[-1,1]\)

- if \(Cor(x,y)>0\), x and y are positively correlated

- if \(Cor(x,y)<0\), x and y are negatively correlated

- Interpretation:

- no interpretation!

- correlation is not causality

- also: data can be correlated by pure chance (spurious correlation)

Examples

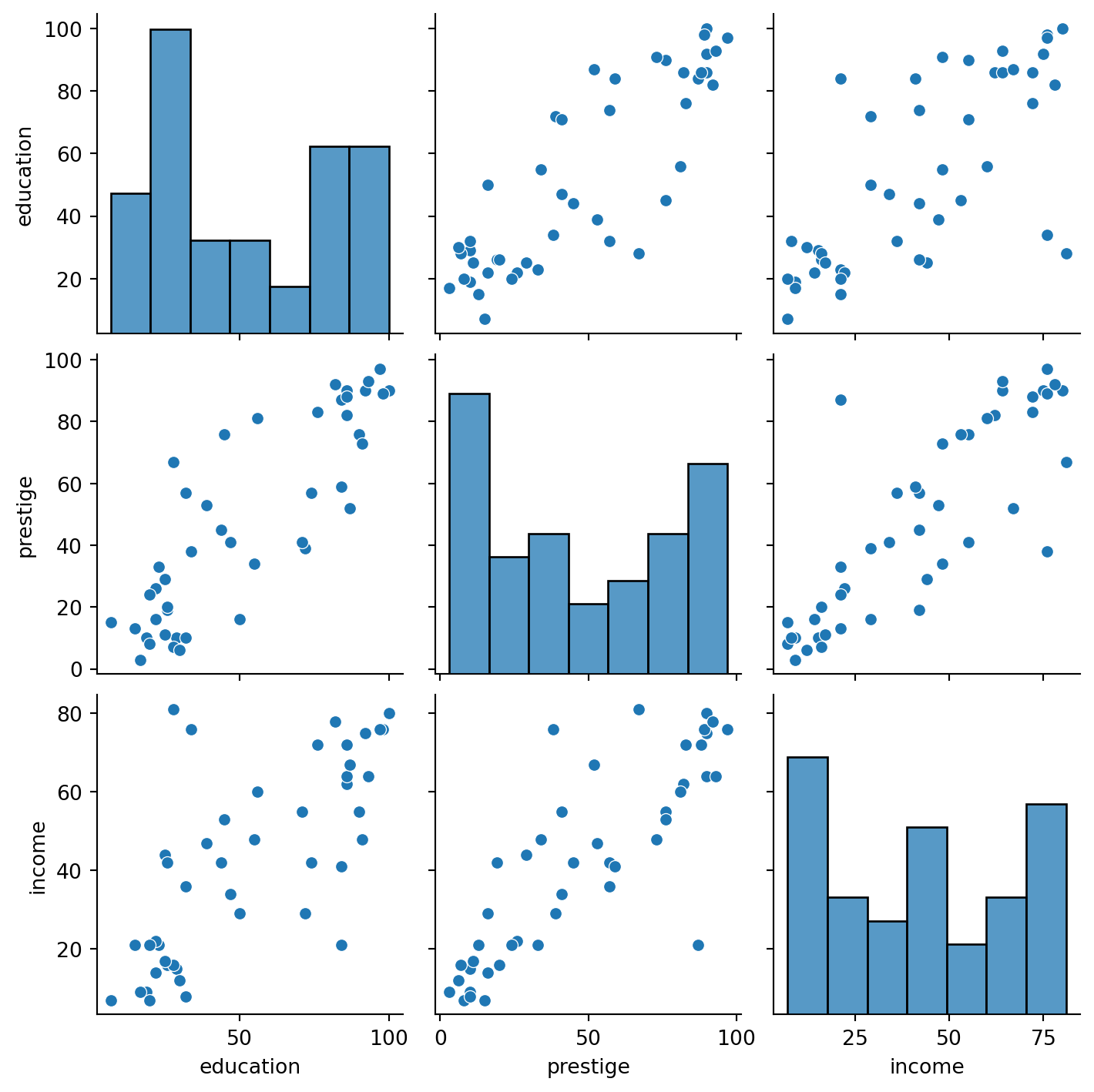

Can we visualize correlations?

Quick

Quick look

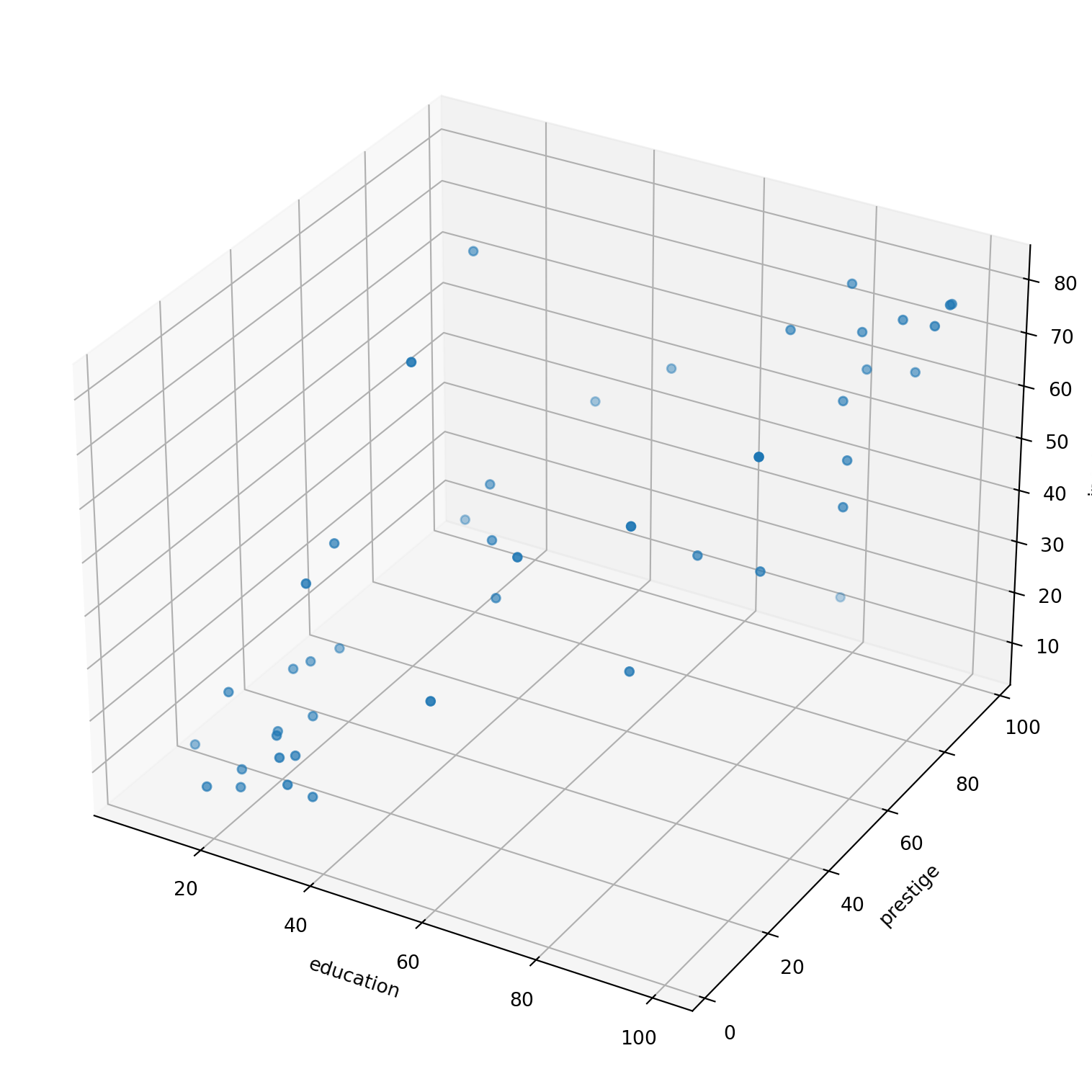

Using matplotlib (3d)

Quick look

The pairplot made with seaborn gives a simple sense of correlations as well as information about the distribution of each variable.

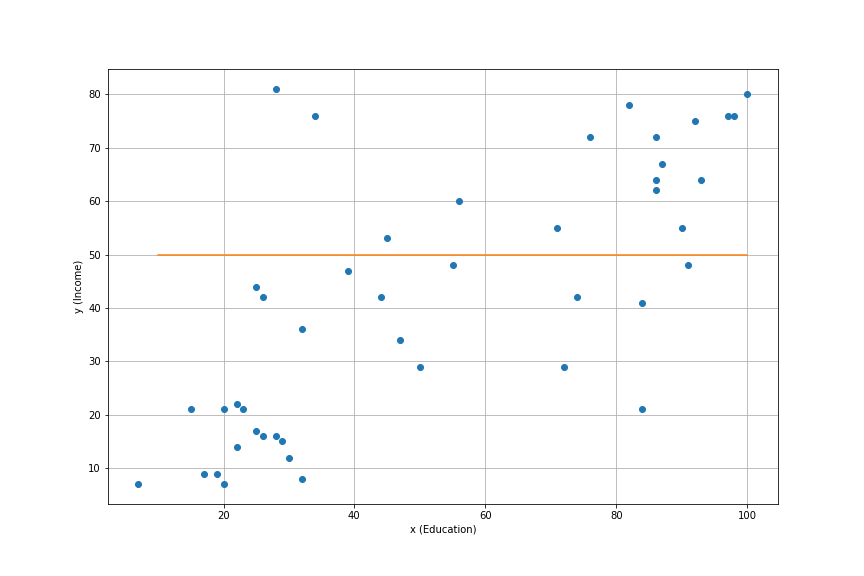

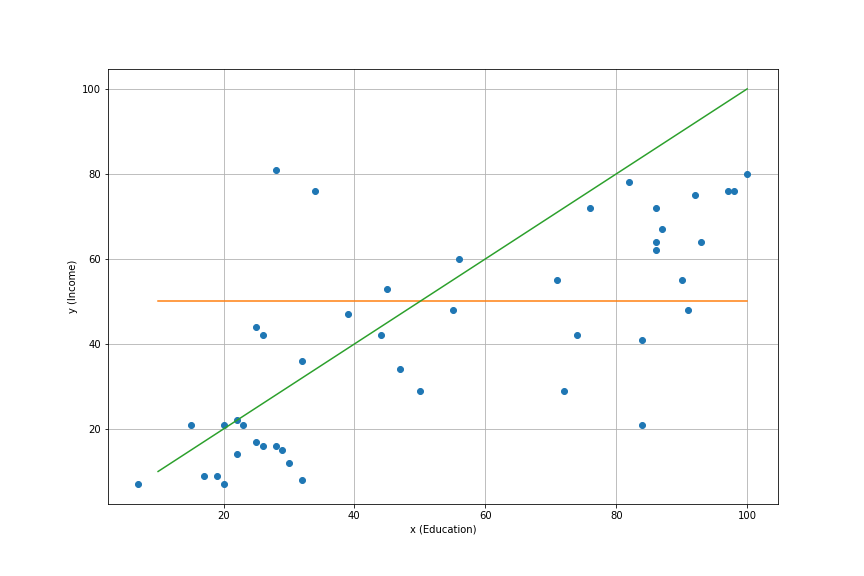

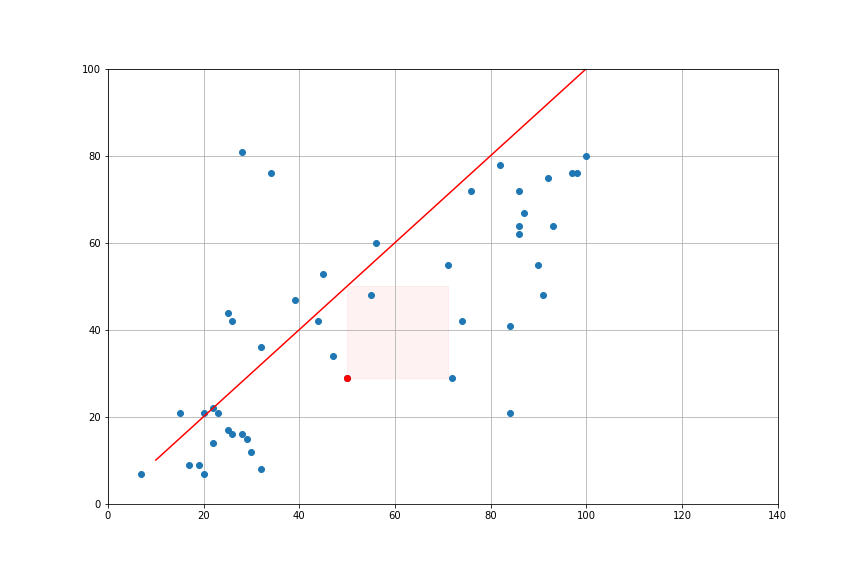

Fitting the data

A Linear Model

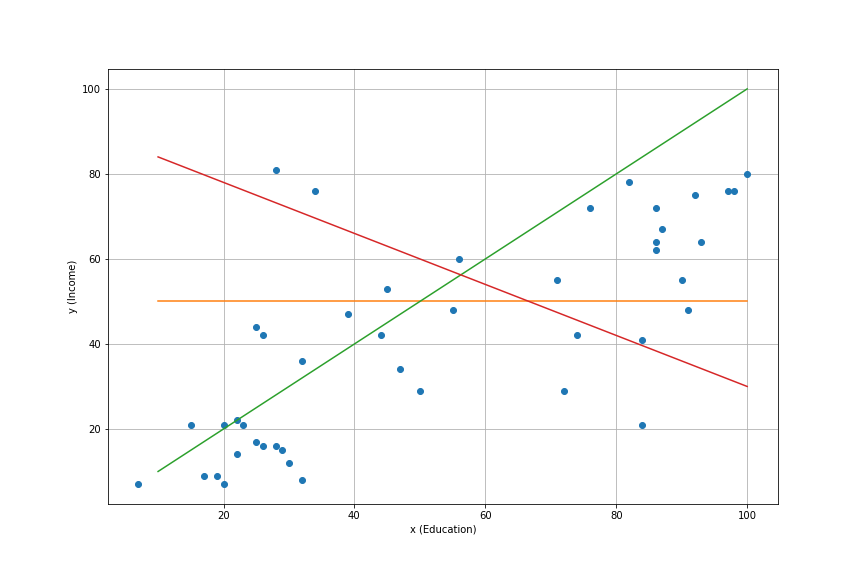

Now we want to build a model to represent the data:

Consider the line: \[y = α + β x\]

Several possibilities. Which one do we choose to represent the model?

We need some criterium.

Least Square Criterium

- Compare the model to the data: \[y_i = \alpha + \beta x_i + \underbrace{e_i}_{\text{prediction error}}\]

- Square Errors \[{e_i}^2 = (y_i-\alpha-\beta x_i)^2\]

- Loss Function: sum of squares \[L(\alpha,\beta) = \sum_{i=1}^N (e_i)^2\]

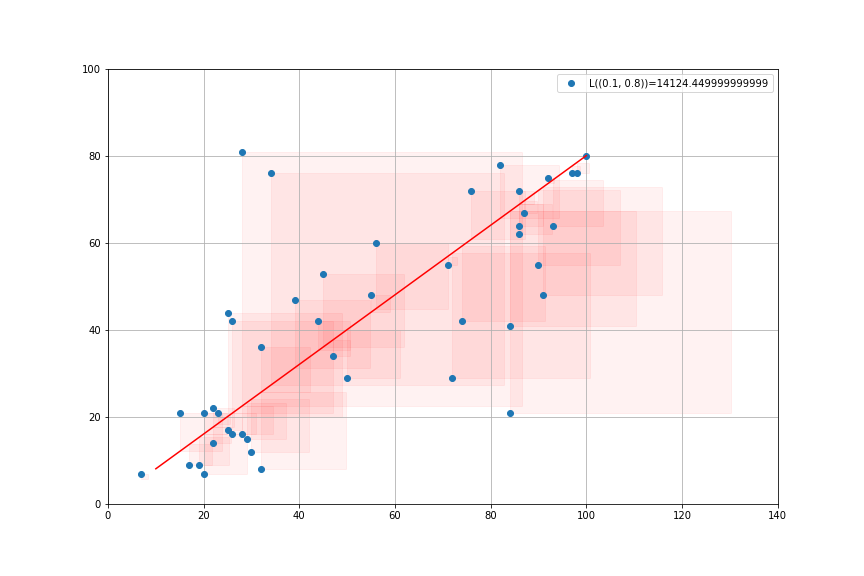

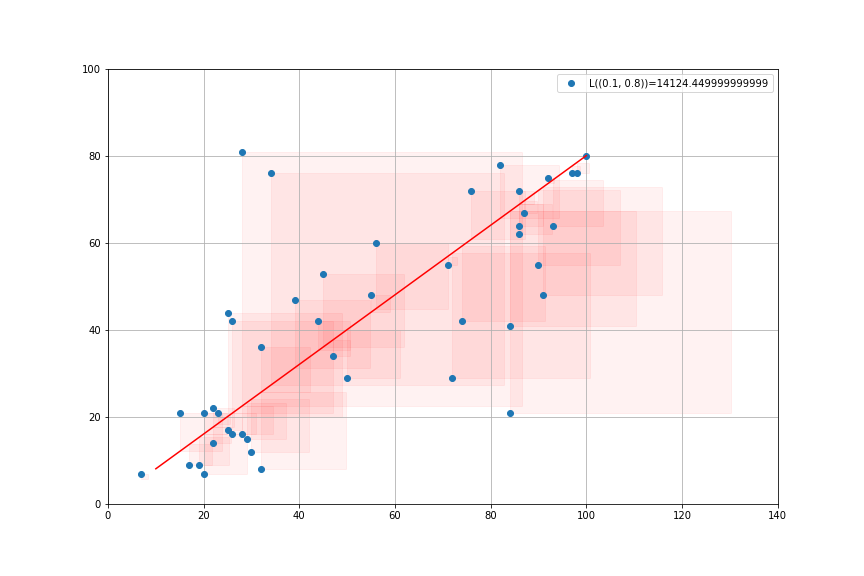

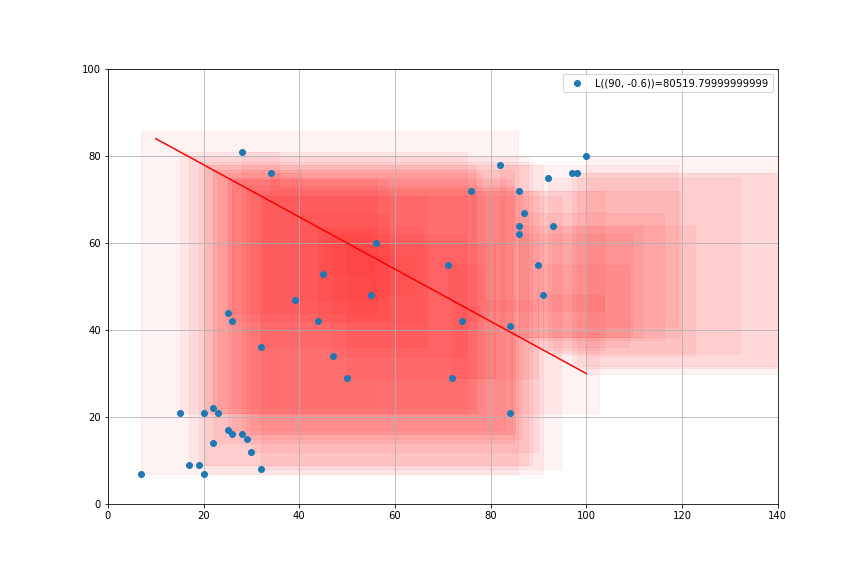

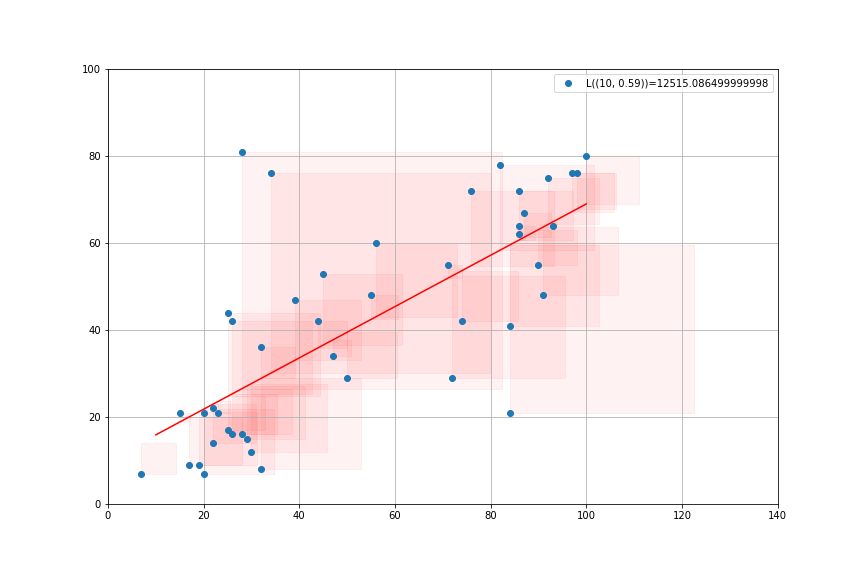

Minimizing Least Squares

- Try to chose \(\alpha, \beta\) so as to minimize the sum of the squares \(L(α, β)\)

- It is a convex minimization problem: unique solution

- This direct iterative procedure is used in machine learning

Ordinary Least Squares (1)

The mathematical problem \(\min_{\alpha,\beta} L(\alpha,\beta)\) has one unique solution1

Solution is given by the explicit formula: \[\hat{\alpha} = \overline{y} - \hat{\beta} \overline{x}\] \[\hat{\beta} = \frac{Cov({x,y})}{Var(x)} = Cor(x,y) \frac{\sigma(y)}{\sigma({x})}\]

\(\hat{\alpha}\) and \(\hat{\beta}\) are estimators.

- Hence the hats.

- More on that later.

Concrete Example

In our example we get the result: \[\underbrace{y}_{\text{income}} = 10 + 0.59 \underbrace{x}_{education}\]

We can say:

- income and education are positively correlated

- a unit increase in education is associated with a 0.59 increase in income

- a unit increase in education explains a 0.59 increase in income

But:

- here explains does not mean cause

Explained Variance

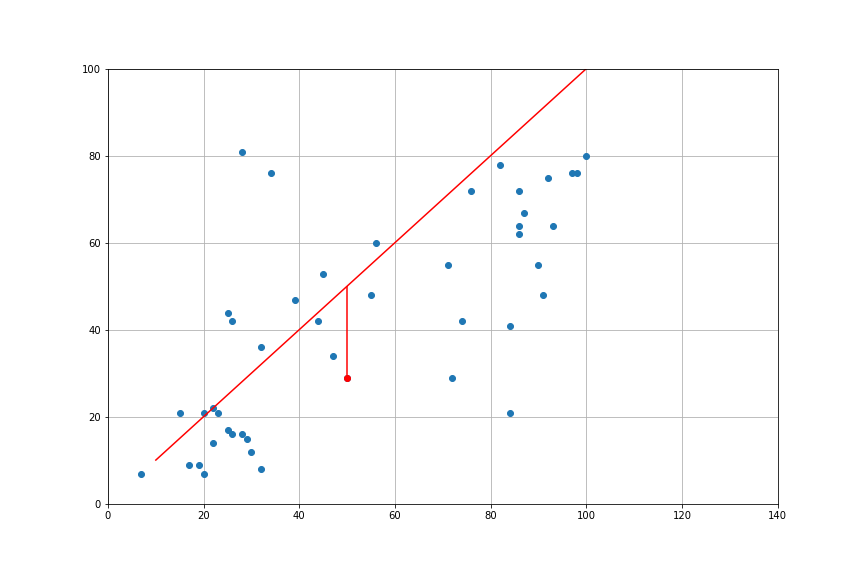

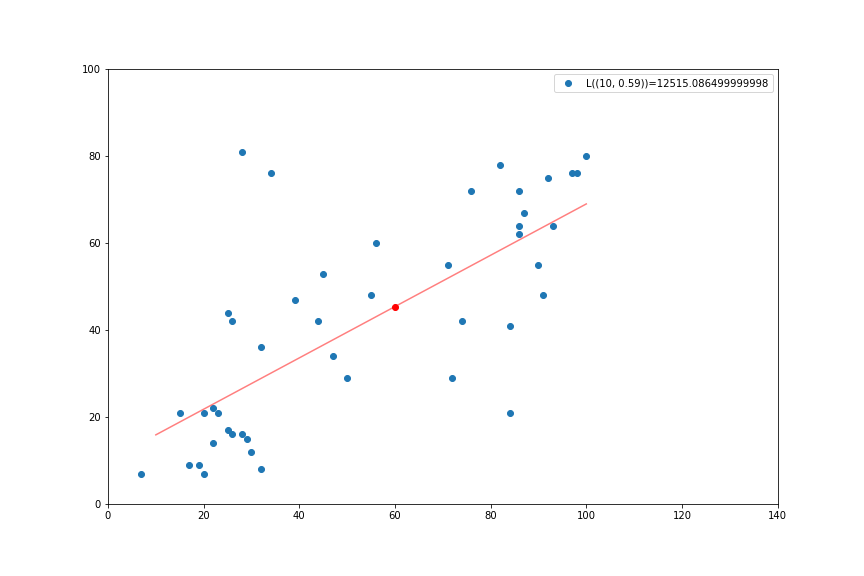

Predictions

It is possible to make predictions with the model:

- How much would an occupation which hires 60% high schoolers fare salary-wise?

- Prediction: salary measure is \(45.4\)

OK, but that seems noisy, how much do I really predict ? Can I get a sense of the precision of my prediction ?

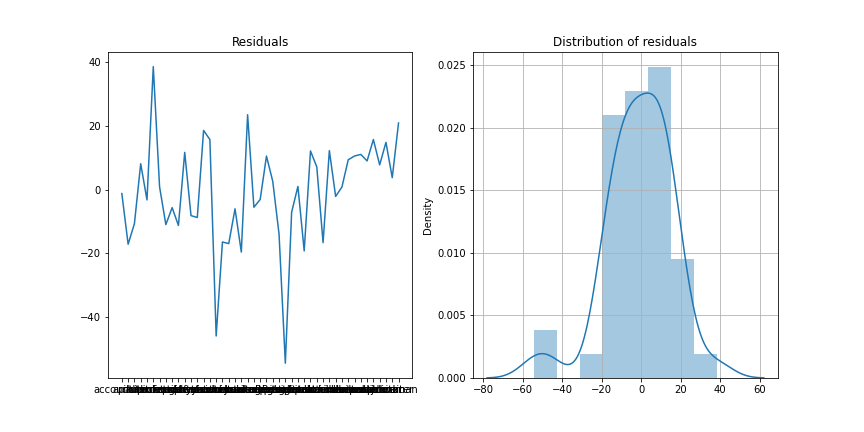

Look at the residuals

- Plot the residuals:

- Any abnormal observation?

- Theory requires residuals to be:

- zero-mean

- non-correlated

- normally distributed

- That looks like a normal distribution

- standard deviation is \(\sigma(e_i) = 16.84\)

- A more honnest prediction would be \(45.6 ± 16.84\)

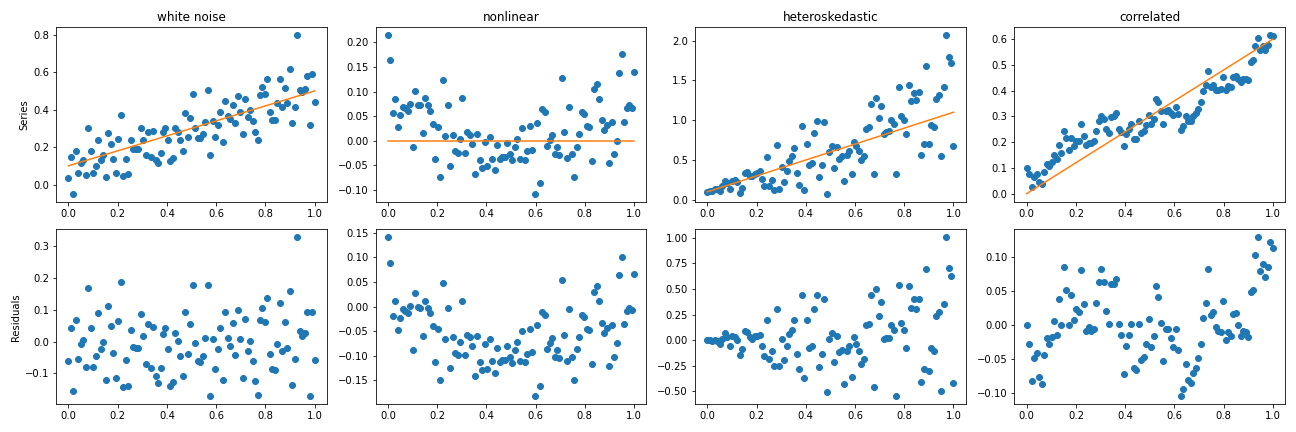

What could go wrong?

- a well specified model, residuals must look like white noise (i.i.d.: independent and identically distributed)

- when residuals are clearly abnormal, the model must be changed

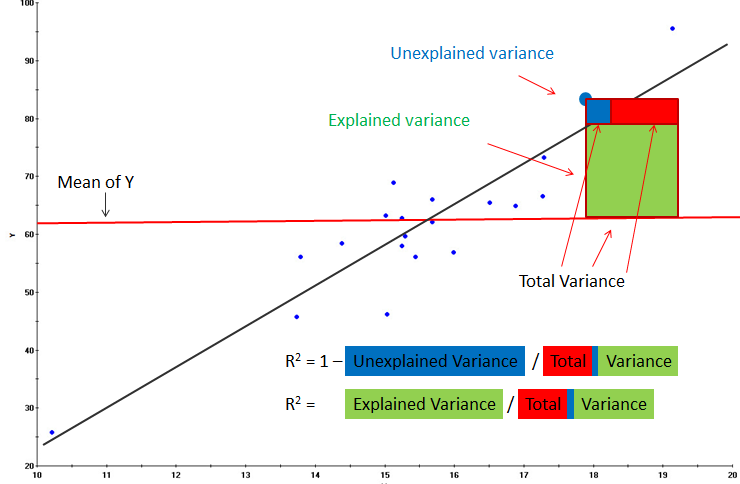

Explained Variance

- What is the share of the total variance explained by the variance of my prediction? \[R^2 = \frac{\overbrace{Var(\hat{\alpha} + \hat{\beta} x_i)}^{ \text{MSS} } } {\underbrace{Var(y_i)}_{ \text{TSS} } } = \frac{MSS}{TSS} = (Cor(x,y))^2\] \[R^2 = 1-\frac{\overbrace{Var(y_i - \hat{\alpha} + \hat{\beta} x_i)}^{\text{RSS}} } { \underbrace{Var(y_i)}_{ {\text{TSS} }}} = 1 - \frac{RSS}{TSS} \]

- MSS: model sum of squares, explained variance

- RSS: residual sum of square, unexplained variance

- TSS: total sum of squares, total variance

- Coefficient of determination is a measure of the explanatory power of a regression

- but not of the significance of a coefficient

- we’ll get back to it when we see multivariate regressions

- In one-dimensional case, it is possible to have small R2, yet a very precise regression coefficient.

Graphical Representation

Statistical inference

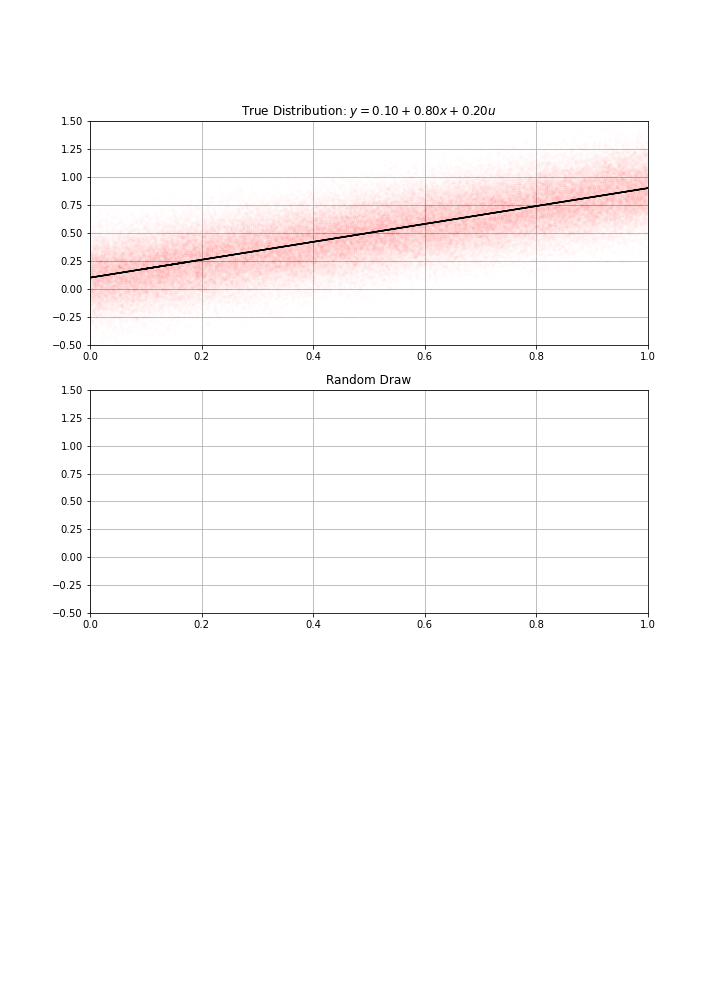

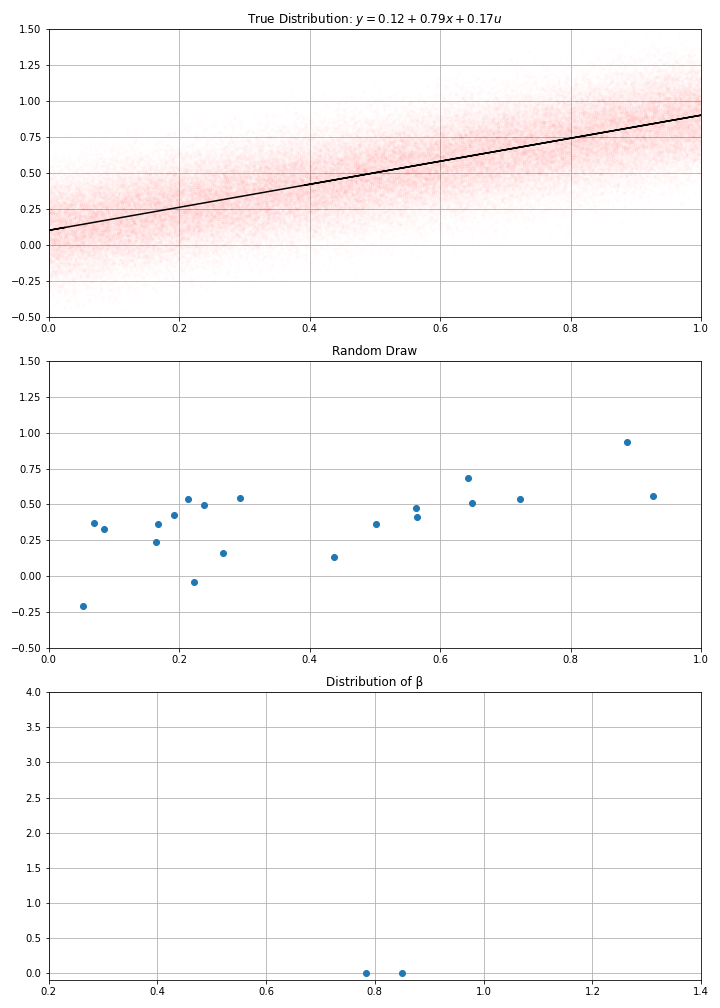

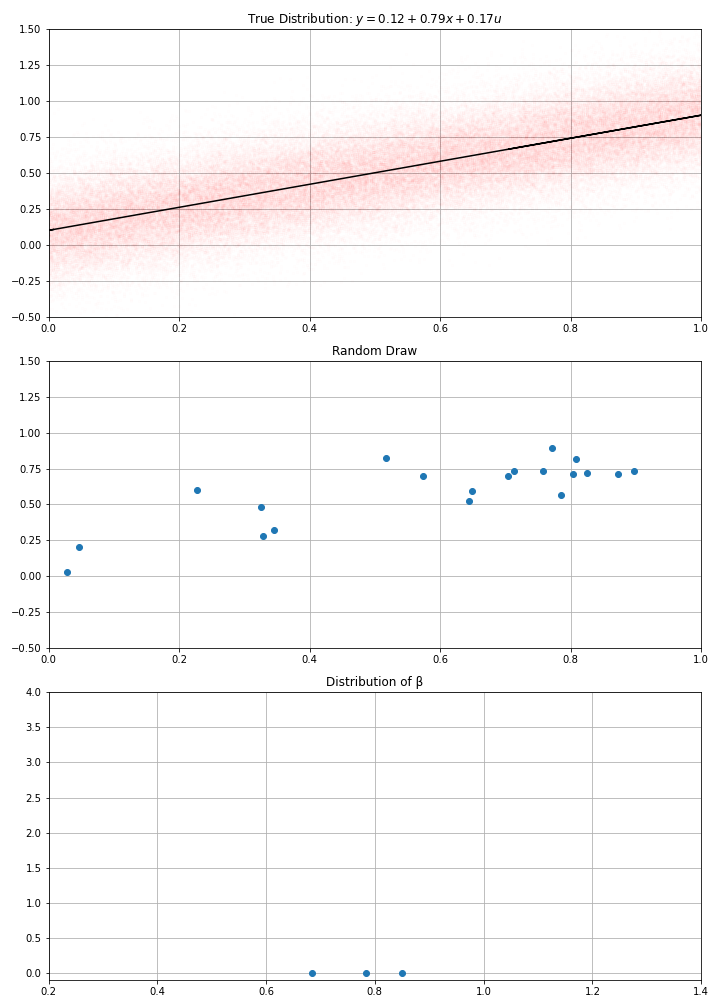

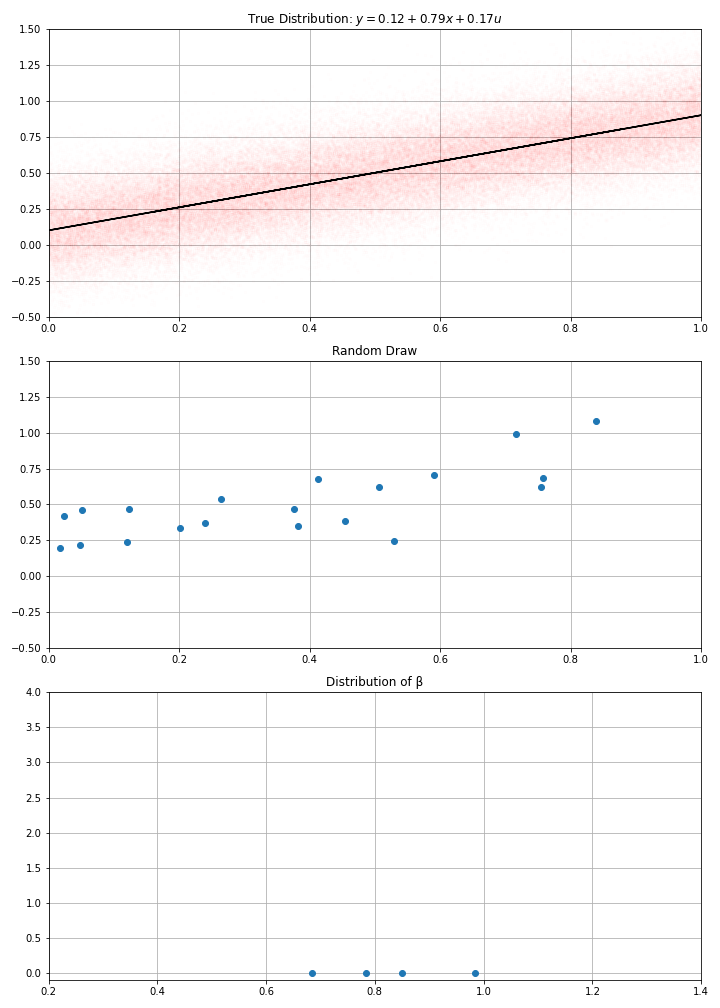

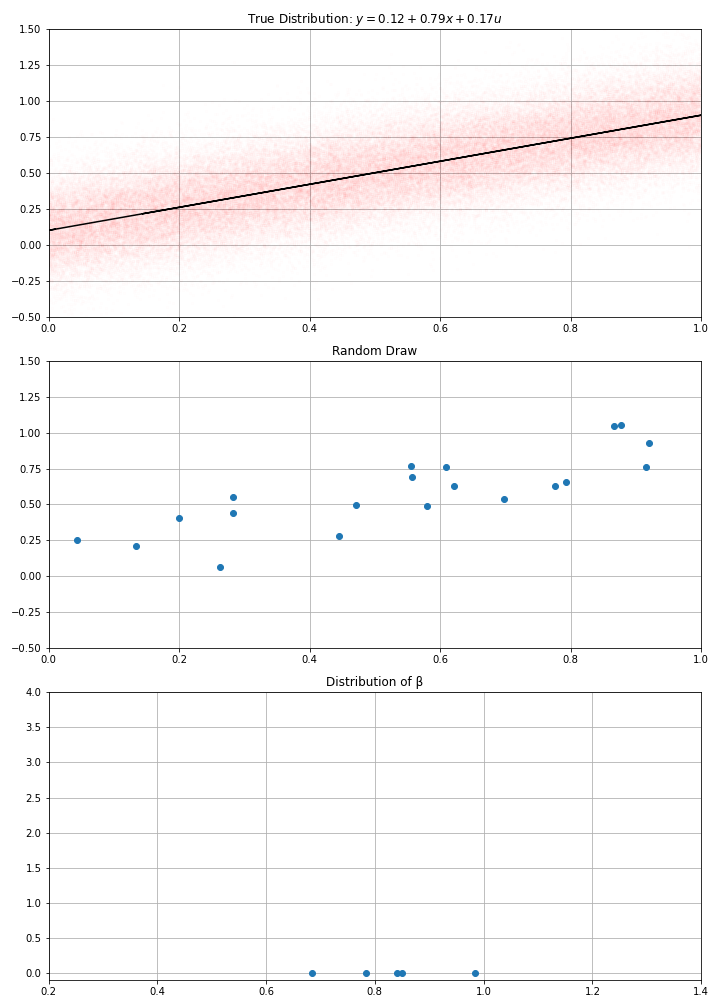

Statistical model

Imagine the true model is: \[y = α + β x + \epsilon\] \[\epsilon_i \sim \mathcal{N}\left({0,\sigma^{2}}\right)\]

- errors are independent …

- and normallly distributed …

- with constant variance (homoscedastic)

Using this data-generation process, I have drawn randomly \(N\) data points (a.k.a. gathered the data)

- maybe an acual sample (for instance \(N\) patients)

- an abstract sample otherwise

Then computed my estimate \(\hat{α}\), \(\hat{β}\)

How confident am I in these estimates ?

- I could have gotten a completely different one…

- clearly, the bigger \(N\), the more confident I am…

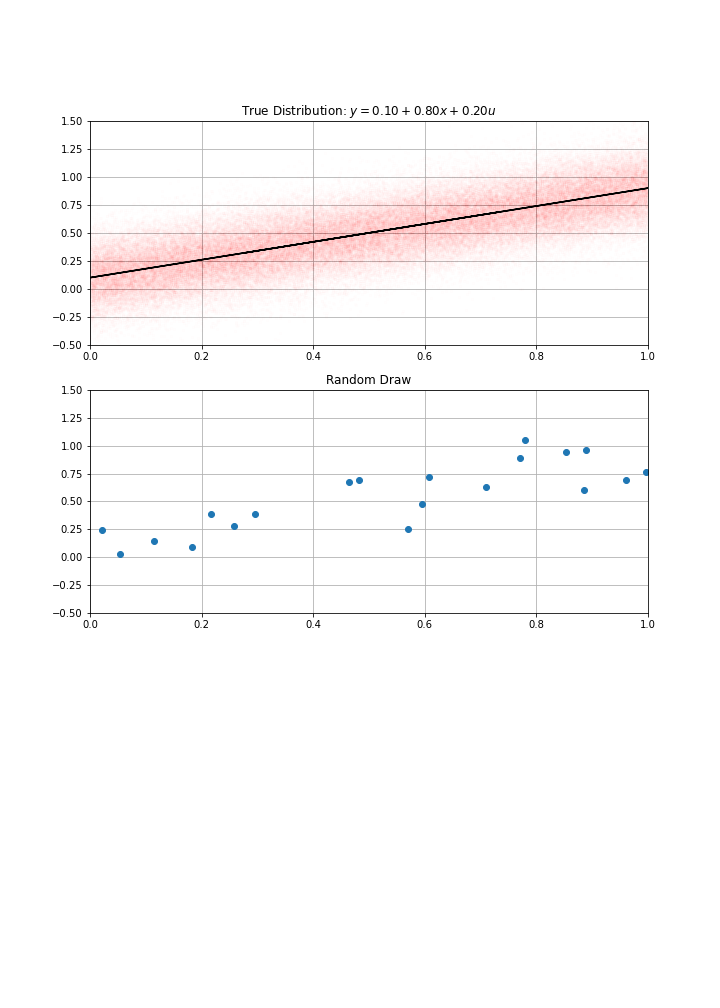

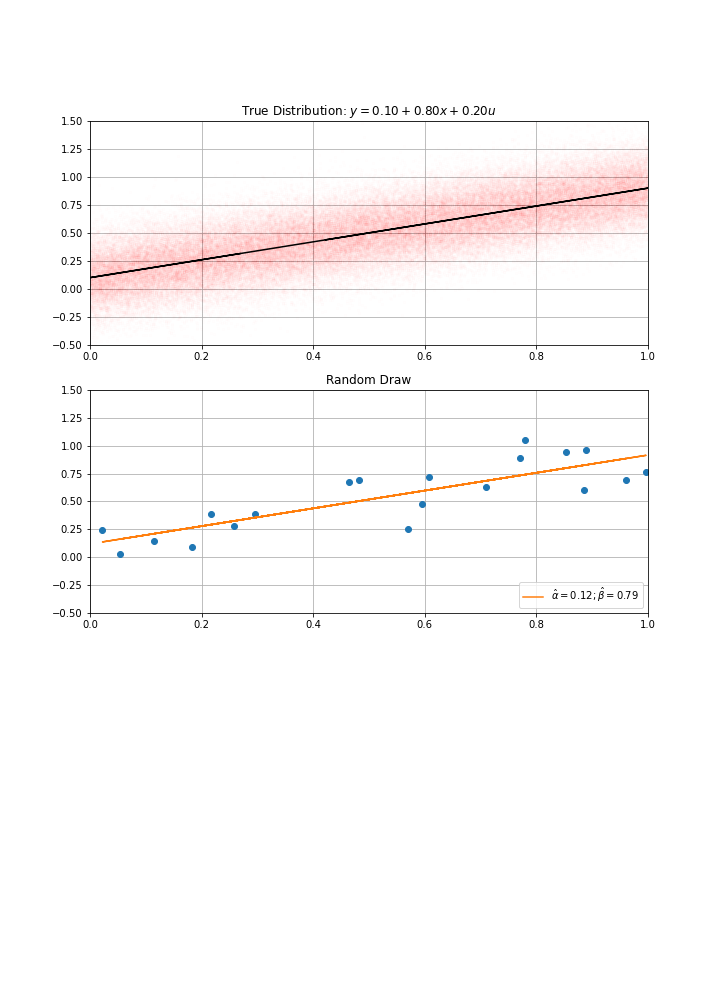

Statistical inference (2)

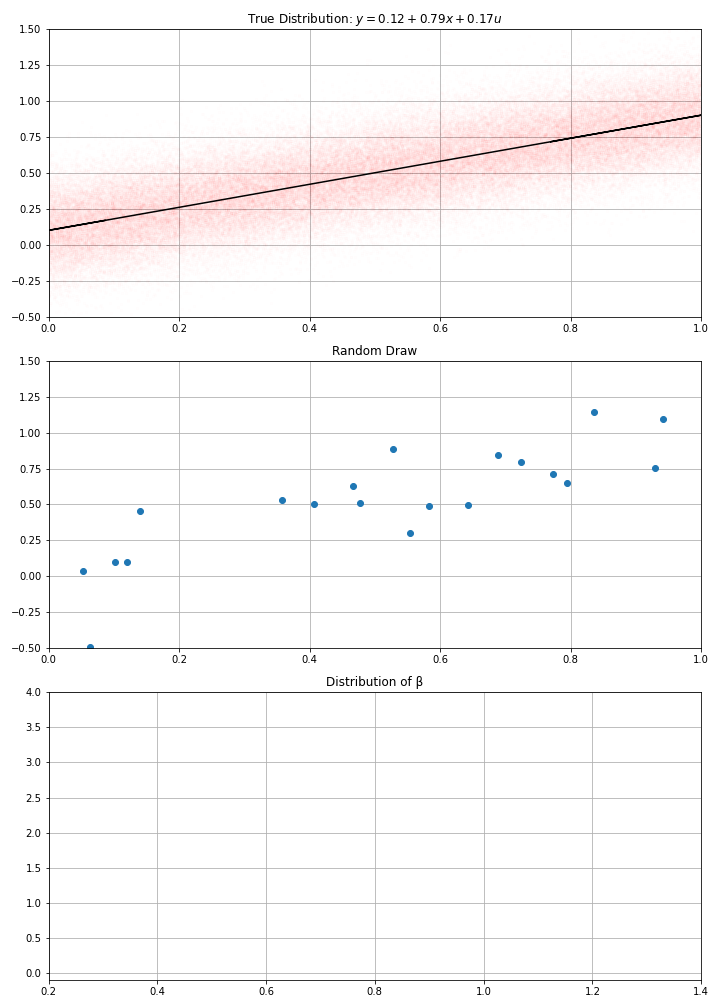

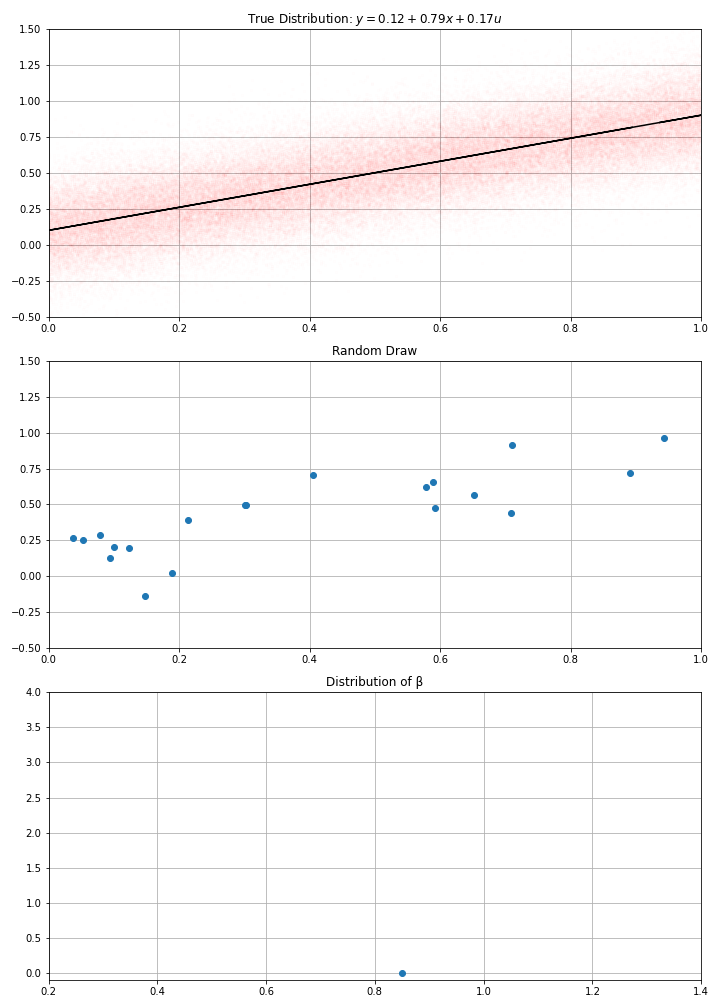

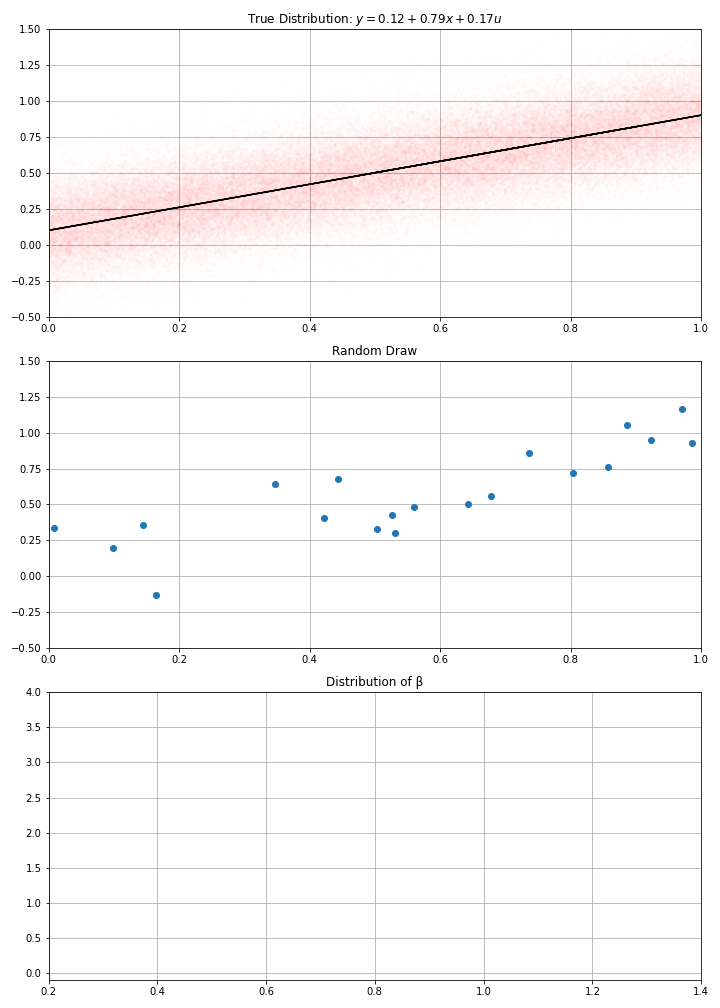

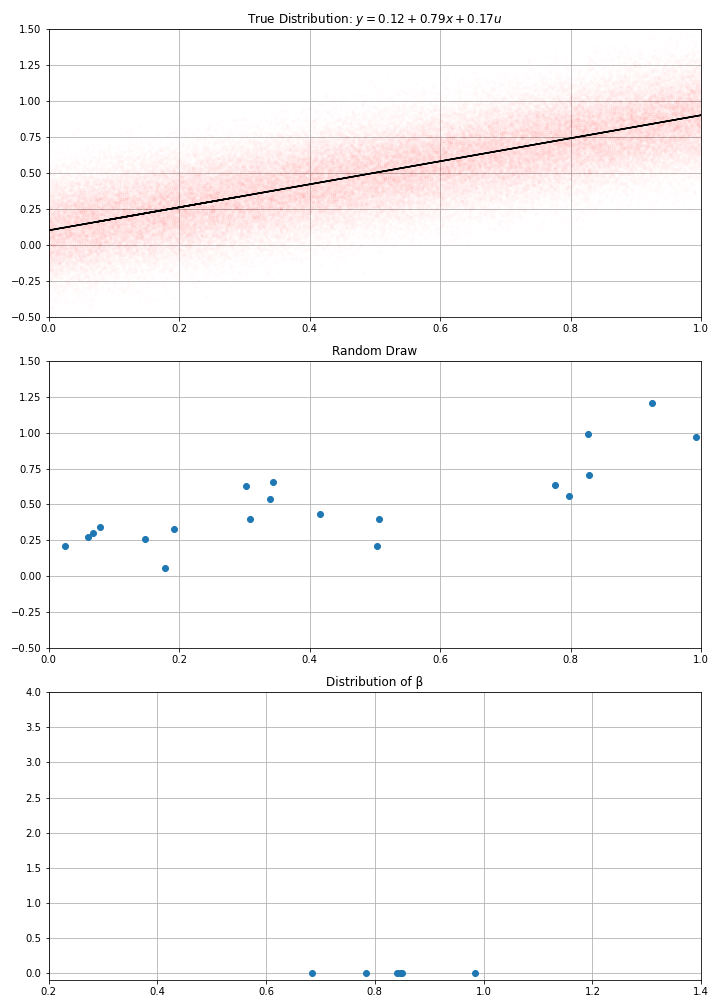

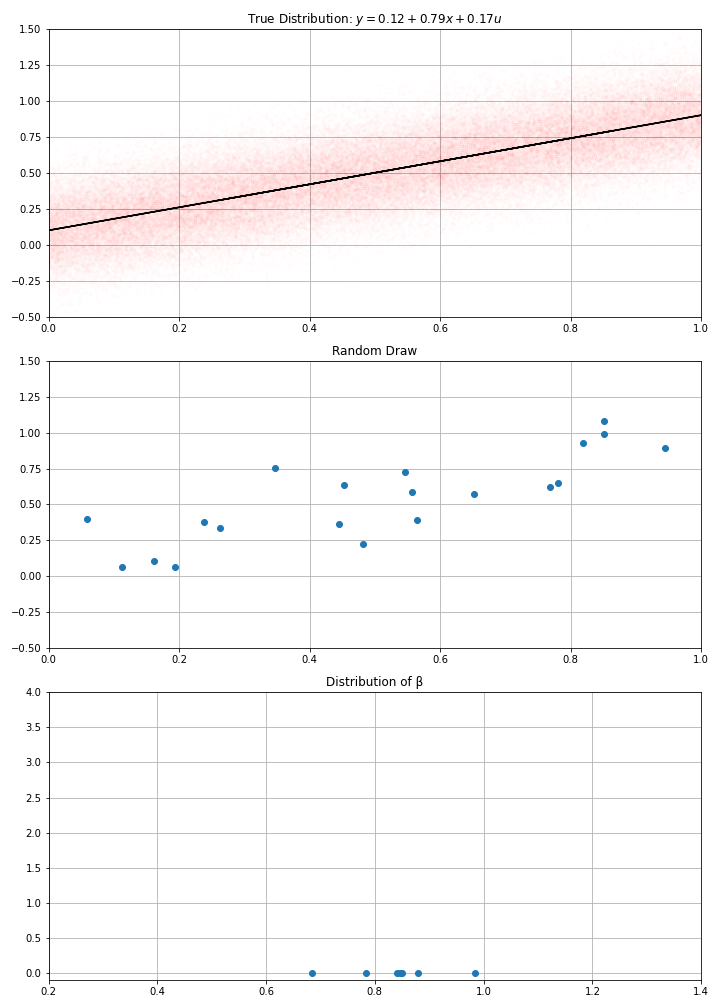

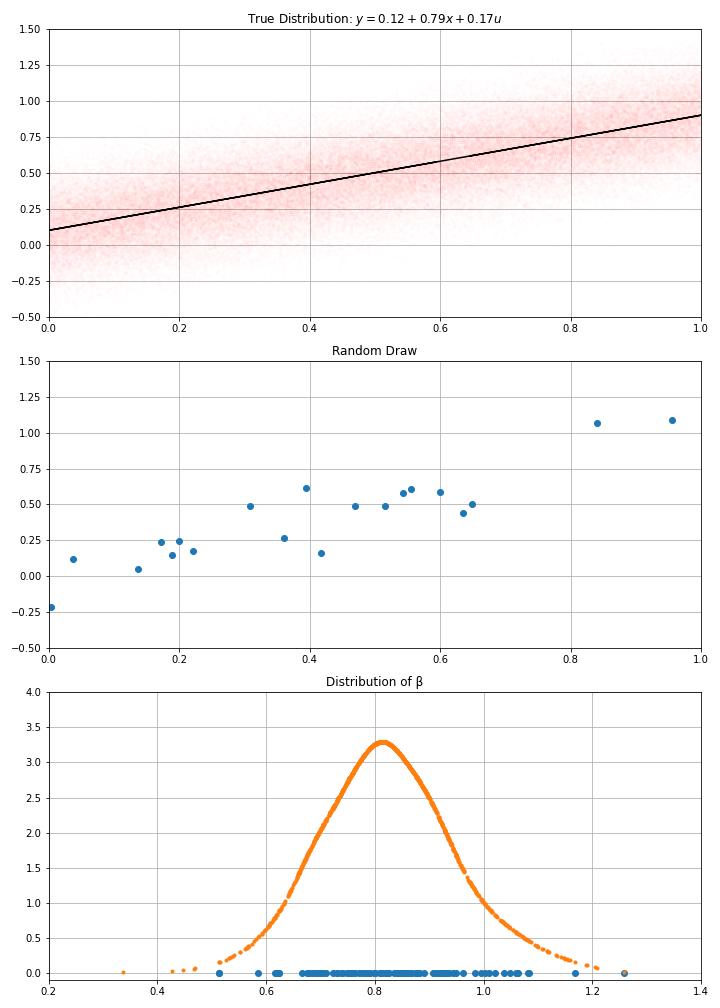

- Assume we have computed \(\hat{\alpha}\), \(\hat{\beta}\) from the data. Let’s make a thought experiment instead.

- Imagine the actual data generating process was given by \(\hat{α} + \hat{\beta} x + \epsilon\) where \(\epsilon \sim \mathcal{N}(0,Var({e_i}))\)

- If I draw randomly \(N\) points using this D.G.P. I get new estimates.

- And if I make randomly many draws, I get a distribution for my estimate.

- I get an estimated \(\hat{\sigma}(\hat{\beta})\)

- were my initial estimates very likely ?

- or could they have taken any value with another draw from the data ?

- in the example, we see that estimates around of 0.7 or 0.9, would be compatible with the data

- How do we formalize these ideas?

- Statistical tests.

First estimates

Given the true model, all estimators are random variables of the data generating process

Given the values \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\sigma\) of the true model, we can model the distribution of the estimates.

Some closed forms:

- \(\hat{\sigma}^2 = Var(y_i - \alpha -\beta x_i)\) estimated variance of the residuals

- \(mean(\hat{\beta}) = \beta\) (unbiased)

- \(\sigma(\hat{\beta}) = \frac{\sigma^2}{Var(x_i)}\)

These statististics or any function of them can be computed exactly, given the data.

Their distribution depends, on the data-generating process

Can we produce statistics whose distribution is known given mild assumptions on the data-generating process?

- if so, we can assess how likely are our observations

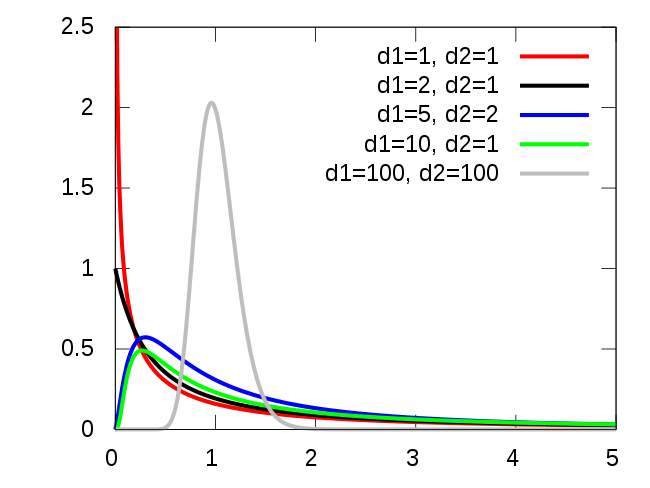

Fisher-Statistic

Test

- Hypothesis H0:

- \(α=β=0\)

- model explains nothing, i.e. \(R^2=0\)

- Hypothesis H1: (model explains something)

- model explains something, i.e. \(R^2>0\)

Fisher Statistics: \[\boxed{F=\frac{Explained Variance}{Unexplained Variance}}\]

Distribution of \(F\) is known theoretically.

- Assuming the model is actually linear and the shocks normal.

- It depends on the number of degrees of Freedom. (Here \(N-2=18\))

- Not on the actual parameters of the model.

In our case, \(Fstat=40.48\).

What was the probability it was that big, under the \(H0\) hypothesis?

- extremely small: \(Prob(F>Fstat|H0)=5.41e-6\)

- we can reject \(H0\) with \(p-value=5e-6\)

In social science, typical required p-value is 5%.

In practice, we abstract from the precise calculation of the Fisher statistics, and look only at the p-value.

Student test

- So our estimate is \(y = \underbrace{0.121}_{\tilde{\alpha}} + \underbrace{0.794}_{\tilde{\beta}} x\).

- we know \(\tilde{\beta}\) is a bit random (it’s an estimator): are we even sure \(\tilde{\beta}\) could not have been zero?

- Student Test: H0: \(\beta=0\), H1: \(\beta \neq 0\)

- Statistics: \(t=\frac{\hat{\beta}}{\sigma(\hat{\beta})}\)

- intuitively: compare mean of estimator to its standard deviation

- also a function of degrees of freedom

- Statistics: \(t=\frac{\hat{\beta}}{\sigma(\hat{\beta})}\)

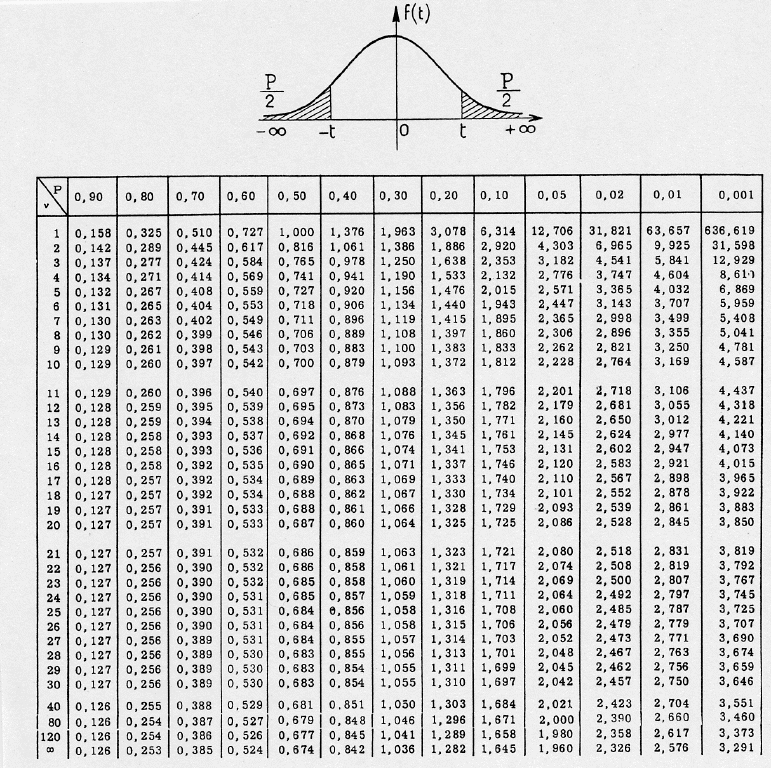

- Significance levels (read in a table or use software):

- for 18 degrees of freedom, \(P(|t|>t^{\star})=0.05\) with \(t^{\star}=1.734\)

- if \(t>t^{\star}\) we are \(95%\) confident the coefficient is significant

Student tables

Confidence intervals

The student test can also be used to construct confidence intervals.

Given estimate, \(\hat{\beta}\) with standard deviation \(\sigma(\hat{\beta})\)

Given a probability threshold \(\alpha\) (for instance \(\alpha=0.05\)) we can compute \(t^{\star}\) such that \(P(|t|>t*)=\alpha\)

We construct the confidence interval: \[I^{\alpha} = [\hat{\beta}-t\sigma(\hat{\beta}), \hat{\beta}+t\sigma(\hat{\beta})]\]

Interpretation (⚠: subtle)

- if the true value was outside of the confidence interval, the probability of obtaining the value that we got would be less than 5%

- if we had repeated the experiment many times and computed the confidence interval, the true value would be inside it 95% of the time

- we can say the true value is within the interval with 95% confidence level

Fact Check

Do more firearms reduce homicide?

Claim (common intuition): “More civilian firearms deter crime ⇒ fewer homicides.”

Simple cross-country OLS (26 high-income countries, early 1990s)

\[\text{HomicideRate}_i = \alpha + \beta\,\text{GunAvailability}_i + \varepsilon_i\]

- Gun availability proxied by the Cook index = average of

(% suicides with a firearm, % homicides with a firearm)

What the bivariate regression finds (Table 2):

- Crude homicide rate: (= 9.2) (p < 0.001), corr = 0.74

- Excluding the U.S.: (= 4.9) (p = 0.003), corr = 0.57

Takeaway: The “more guns → less homicide” claim is not supported by this simple cross-country correlation.

⚠️ Caution (OLS lesson): This is not causal (possible confounding, reverse causality, measurement error). Use it to practice interpreting (), p-values, and thinking about omitted variables.

Source: Hemenway, D. & Miller, M. (2000). Firearm Availability and Homicide Rates across 26 High-Income Countries. Journal of Trauma, 49(6), 985–988. Paper